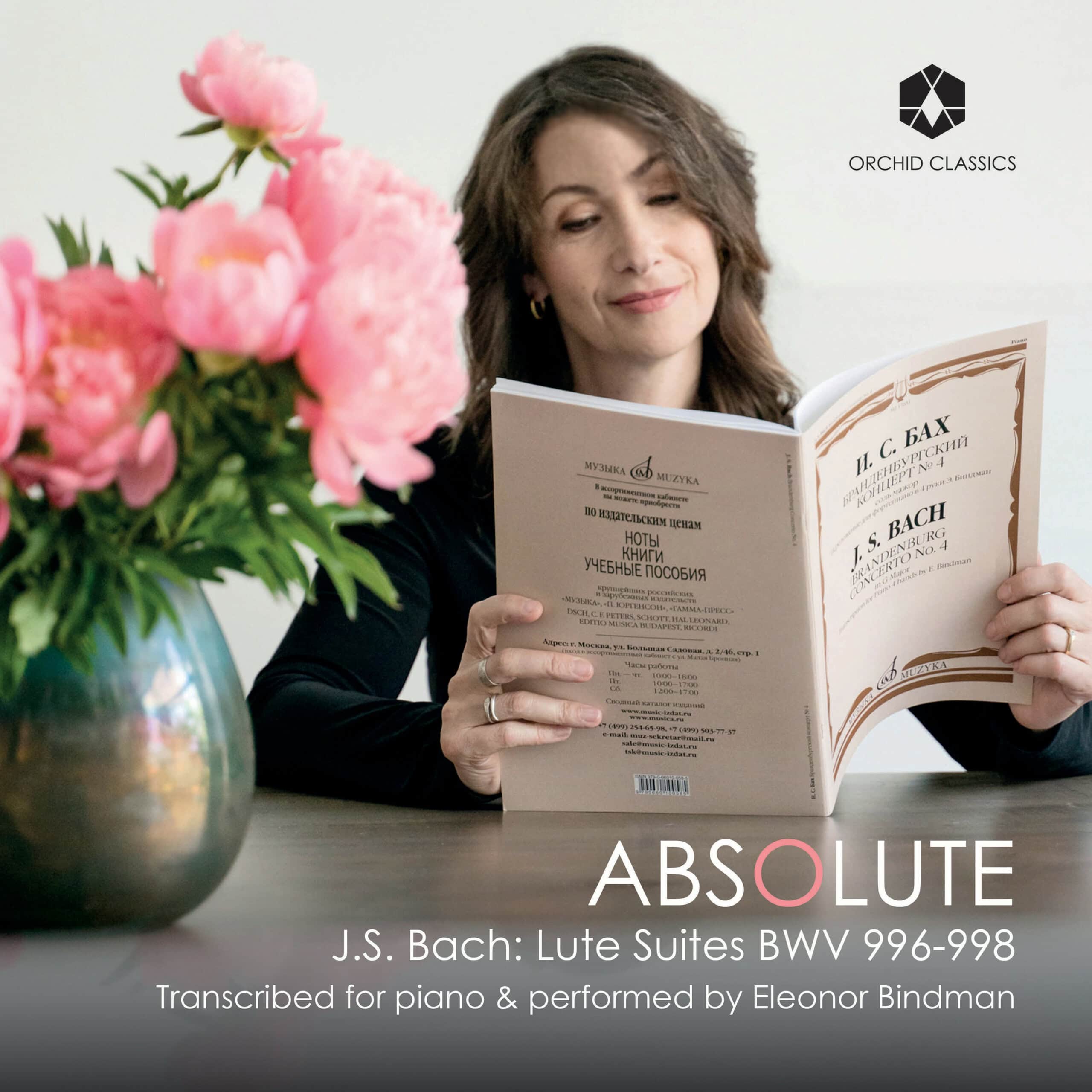

Absolute

J.S. Bach: Lute Suites BWV 996-998

Transcribed for piano and performed by Eleonor Bindman

In this new album from pianist Eleonor Bindman, works by J.S. Bach originally composed for the lautenwerk (lute-harpsichord) are presented in piano transcriptions, offering a fresh perspective on some rarely explored masterpieces.

Highlights include BWV 997 and 998, featuring stunning fugues with ornate middle sections unlike typical keyboard fugues, and a heartfelt arrangement of “Betrachte, meine Seele” from St. John’s Passion, which serves as a moving conclusion to the album.

Fans of Eleonor Bindman’s previous transcriptions – such as The Brandenburg Duets and The Cello Suites – will appreciate this latest addition to the pianist’s catalogue, recorded on a Bösendorfer piano which truly captures the remarkable richness of Bach’s writing.

Eleonor Bindman writes, ‘Transcriptions can revive interest in original compositions, and I am hoping that a piano version of Bach’s Suites BWV 996, 997, and 998 will increase their popularity. There is no consensus as to exactly what instrument each suite was designated for, but the choices narrow down to either the lute or the lute-harpsichord, an instrument then known as “lautenwerck.” Existing autographs and manuscripts are mostly in staff notation with a few lute tablatures since only professional lute players could produce those. Recorded versions are usually titled “lute suites” and performed either by guitarists, lutenists, or harpsichordists. Just like Bach’s other solo collections, these suites present a technical and musical tour de force for their performers and deserve their rightful place alongside Bach’s suites for keyboard, violin, and cello.’

Tracks:

- Prelude: Passaggio – Presto

- Allemande

- Courante

- Sarabande

- Bourrée

- Gigue

- Prelude

- Fugue

- Sarabande

- Gigue

- Double

- Prelude

- Fugue

- Allegro

- “Betrachte, meine Seel” from St. John’s Passion, BWV 245

Liner Notes:

Buy/Listen:

J.S. Bach Orchestral Suites: Transcribed for piano duet

Eleonor Bindman’s new arrangement of Bach’s Orchestral Suites for piano duet follows her widely admired recording of the six Brandenburg Concertos. Once again, the transcription reimagines Bach’s writing using the modern piano, in this case a Bösendorfer. Bindman and her Duo Vivace partner, Susan Sobolewski, draw upon the suite’s dance movements to suggest how Bach might have distributed the material, ordering them for maximum contrast, and succeeding in conveying the music’s vitality and beauty in a new medium.

Tracks:

- I. Ouverture

- II. Air

- III. Gavotte I – II

- IV. Bourrée

- V. Gigue

- I. Ouverture

- II. Rondeau

- III. Sarabande

- IV. Bourrée I – II

- V. Polonaise – Double

- VI. Menuet

- VII. Badinerie

- I. Ouverture

- II. Bourrée I – II

- III. Gavotte

- IV. Menuet I – II

- V. Réjouissance

- I. Ouverture

- II. Courante

- III. Gavotte I – II

- IV. Forlane

- V. Menuet I – II

- VI. Bourrée I – II

- VII. Passepied I – II

Liner Notes:

Reviews:

Buy/Listen:

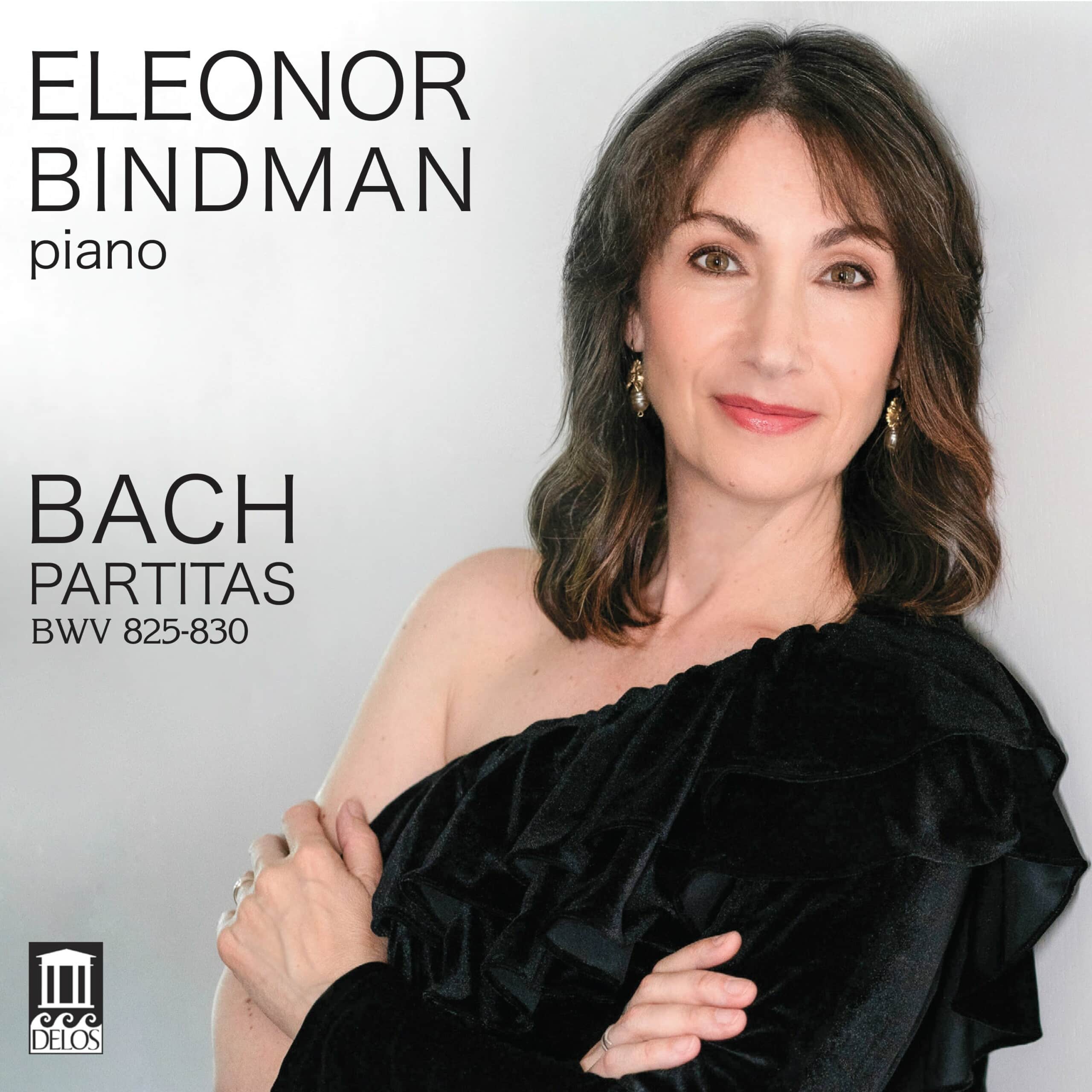

J.S. Bach: Partitas BWV 825-830

The profound and delightful Partitas, J. S. Bach’s Opus 1, sparkle in Eleonor Bindman’s brilliant performance. Her unhurried tempos bring out the twists, turns and quick modulations of the dance movements and preludes of this unparalleled set of six suites — famous in Bach’s day and today for their vitality and depth. Bindman’s spirited recording enriches the listener’s experience by revealing the power and emotional nuances of the suites.

The scope of the Partitas is vast — melody, harmony and counterpoint blending in sonorous combinations that surprise, fascinate and enchant. In the words of Bach’s first biographer, J. N. Forkel: “Such excellent compositions for the clavier [keyboard] had never been seen and heard before. Anyone who had learnt to perform well some pieces out of them could make his fortune in the world thereby.” Choosing to publish this set as his Opus 1, Bach clearly held these compositions in high esteem.

Tracks:

- Partita I in B-flat Major, BWV 825: Praeludium

- Partita I in B-flat Major, BWV 825: Allemande

- Partita I in B-flat Major, BWV 825: Corrente

- Partita I in B-flat Major, BWV 825: Sarabande

- Partita I in B-flat Major, BWV 825: Menuets I and II

- Partita I in B-flat Major, BWV 825: Gigue

- Partita II in C Minor, BWV 826: Sinfonia

- Partita II in C Minor, BWV 826: Allemande

- Partita II in C Minor, BWV 826: Courante

- Partita II in C Minor, BWV 826: Sarabande

- Partita II in C Minor, BWV 826: Rondeaux

- Partita II in C Minor, BWV 826: Capriccio

- Partita VI in E Minor, BWV 830: Toccata

- Partita VI in E Minor, BWV 830: Allemande

- Partita VI in E Minor, BWV 830: Corrente

- Partita VI in E Minor, BWV 830: Air

- Partita VI in E Minor, BWV 830: Sarabande

- Partita VI in E Minor, BWV 830: Tempo di Gavotta

- Partita VI in E Minor, BWV 830: Gigue

- Partita III in A Minor, BWV 827: Fantasia

- Partita III in A Minor, BWV 827: Allemande

- Partita III in A Minor, BWV 827: Corrente

- Partita III in A Minor, BWV 827: Sarabande

- Partita III in A Minor, BWV 827: Burlesca

- Partita III in A Minor, BWV 827: Scherzo

- Partita III in A Minor, BWV 827: Gigue

- Partita IV in D Major, BWV 828: Ouverture

- Partita IV in D Major, BWV 828: Allemande

- Partita IV in D Major, BWV 828: Courante

- Partita IV in D Major, BWV 828: Aria

- Partita IV in D Major, BWV 828: Sarabande

- Partita IV in D Major, BWV 828: Menuet

- Partita IV in D Major, BWV 828: Gigue

- Partita V in G Major, BWV 829: Preambulum

- Partita V in G Major, BWV 829: Allemande

- Partita V in G Major, BWV 829: Corrente

- Partita V in G Major, BWV 829: Sarabande

- Partita V in G Major, BWV 829: Tempo di Minuetta

- Partita V in G Major, BWV 829: Passepied

- Partita V in G Major, BWV 829: Gigue

Liner Notes:

Reviews:

Buy/Listen:

J.S. Bach Cello Suites for Solo Piano Recording

On the heels of the recent recording – “breathtaking in its sheer precision and vitality” (Pianist magazine) – of her own transcription for four-hands piano of J.S. Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, pianist Eleonor Bindman has now completed a new project: a solo piano transcription and recording of all six of Bach’s suites for unaccompanied cello. These pieces have been transcribed many times for instruments from trombone to charango, starting with the lute version of Suite No. 5 made by Bach himself. But previous piano versions, particularly in the 19th century, tended toward “improvements” ranging from added harmonies to newly composed accompaniments. Bindman’s goal was to adhere as closely to the original works as possible, making a simple and sincere attempt to bring a new sonority to some of Bach’s most beautiful conceptions. The new recording will be released on the Grand Piano label, a subsidiary of Naxos, on October 9.

Each of the cello suites begins with a prelude, followed by a series of movements named after dances but not always especially danceable; Bach treated these forms with great flexibility. Thus Bindman’s immersion in the cello suites was partially a process of discovering the organic personality of each movement, distinct from the other examples of that dance in the other suites. In some cases the mechanics of the piano affected her interpretation: for example, she tended toward slightly faster tempos than a cellist would be inclined to take. Tonalities also proved to be an important consideration: the E-flat key of Suite No. 4, for example, is notably idiomatic for the piano – doubly so on Bindman’s richly resonant Bösendorfer – despite being a difficult key for the work’s original instrument. A video of Bindman playing the Prelude from Suite No. 1 can be seen here.

Among Bindman’s motivations was the desire to make the music accessible to amateur pianists, for whom these single-voice masterpieces can now be an experience of the beauty and structure of Bach’s music without the problems of coordination that can make even the simplest two-part inventions a daunting challenge. Fortuitously, the current pandemic-imposed limitations on the fine arts and human contact make this part of her purpose even more significant. As she says:

“I am especially happy about introducing these new arrangements to amateur pianists. As a teacher I have found working with adults particularly gratifying, because they are actively looking for ways to grow and participate and enjoy their lives. I want to give those pianists access to this great music without the bar being so high they feel unequal to it. These pieces certainly make excellent technical exercises, but they can also shift the attention from mechanics to cultivating tone and expression, to training the ear. The practice of listening to oneself is the only true path to musicianship. If this arrangement helps someone along this path, my goal will be accomplished.”

Another of Bindman’s recent projects was the publication of a piano book called Stepping Stones to Bach – 24 intermediate piano arrangements of the Baroque master’s most famous tunes – that included three movements from the cello suites and proved to be a stepping stone to the transcription of the entire set. Bach would probably have approved; as shown by his Well-Tempered Clavier, the purposes of music-making and technical studies can often overlap, so a project with a foot in both worlds can boast a good pedigree.

“Bach himself regularly transcribed his own and other composers’ music and created different instrumental versions of the same piece. This transcribing practice has persisted and is still very much alive. … The resulting musical statement may be a faithful reproduction …, a transformation beyond recognition or something in between. Regardless of the outcome, the original source is of such exceptional depth and appeal that for the past three centuries it attracted a steady stream of pilgrims, ready to sacrifice their time and energy for the joy of communion.”

Explore the Bach Cello Suites for Solo Piano Project Page

Tracks:

-

CELLO SUITE NO. 1 IN G MAJOR, BWV 1007

- I. Prelude

- II. Allemande

- III. Courante

- IV. Sarabande

- V. Menuets I–II

- VI. Gigue CELLO SUITE NO. 2 IN D MINOR, BWV 1008

- I. Prelude

- III. Allemande

- III. Courante

- IV. Sarabande

- V. Menuets I–II

- VI. Gigue CELLO SUITE NO. 3 IN C MAJOR, BWV 1009

- I. Prelude

- II. Allemande

- III. Courante

- IV. Sarabande

- V. Bourrées I–II

- VI. Gigue

-

CELLO SUITE NO. 4 IN E FLAT MAJOR, BWV 1010

- I. Prelude

- II. Allemande

- III. Courante

- IV. Sarabande

- V. Bourrées I–II

- VI. Gigue CELLO SUITE NO. 5 IN C MINOR, BWV 1011

- I. Prelude

- II. Allemande

- III. Courante

- IV. Sarabande

- V. Gavottes I–II

- VI. Gigue CELLO SUITE NO. 6 IN D MAJOR, BWV 1012

- I. Prelude

- II. Allemande

- III. Courante

- IV. Sarabande

- V. Gavottes I–II

- VI. Gigue

Liner Notes:

Reviews:

Buy/Listen:

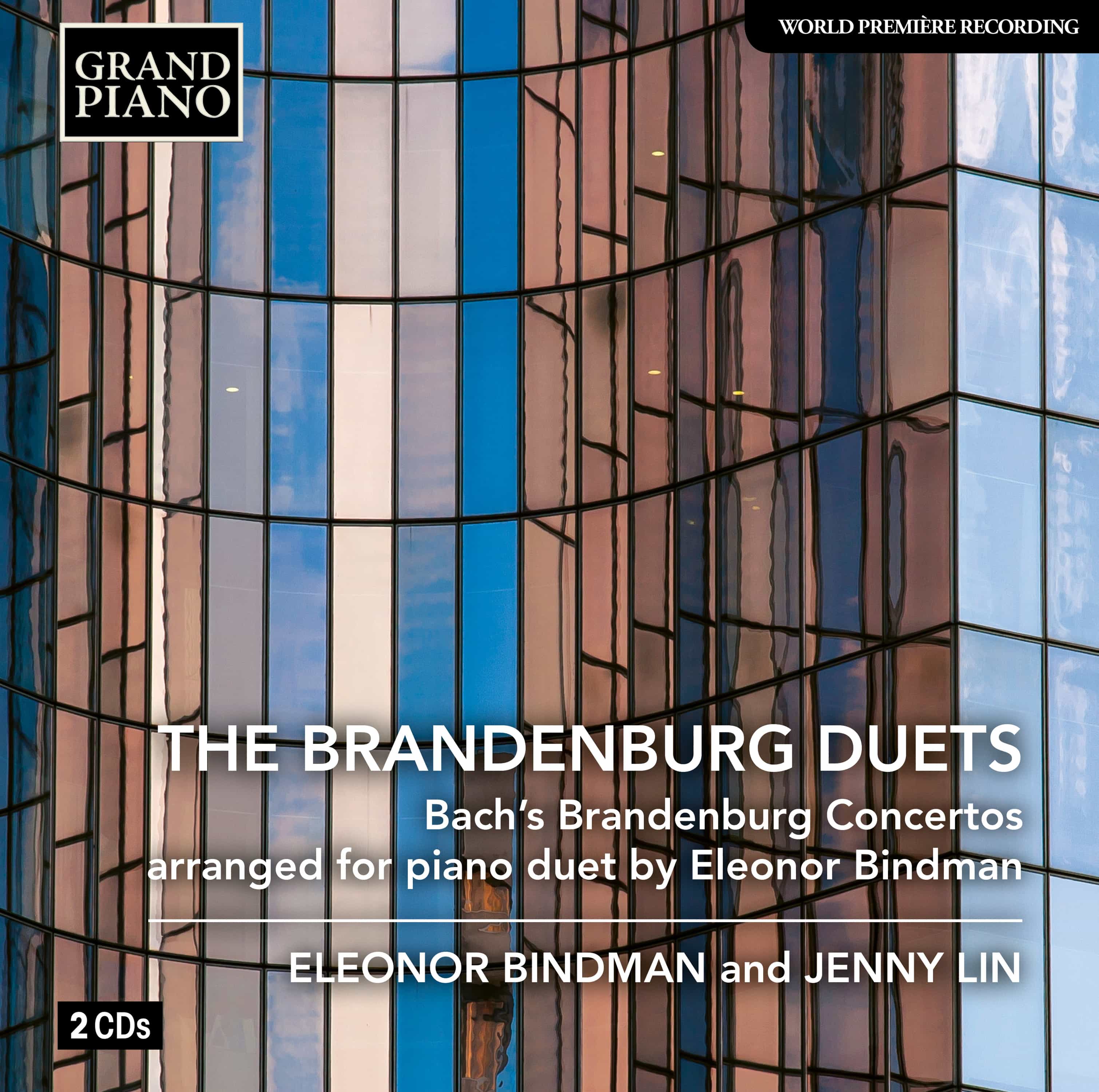

The Brandenburg Duets

“The existing Piano Duet transcription of the Brandenburg Concertos proved to be of no avail to musicians so I felt compelled to create an accessible arrangement, one that could place these masterpieces into the heart of the piano-four-hands repertoire next to Mozart’s Sonatas and Schubert’s works. By recording the Brandenburg Duets, I hope to attract fresh attention to the art of partnership on one keyboard and to inspire amateur and professional pianists alike to engage in music-making of the highest order. We can never have too much Bach.” – Eleonor Bindman

Unlike the only published piano duet arrangement by Max Reger, which has serious performance limitations, Eleonor Bindman’s new transcription of the Brandenburg Concertos highlights their polyphony, imagining how Bach might have distributed the score if he had created four-part inventions for piano duet. With an equal partnership between the two instrumentalists, using the modern piano’s full potential to convey the unique scoring and character of each work, the concertos are ordered to create an engaging listening sequence.

Explore the Brandenburg Duets Project Page

Tracks:

-

- I. Allegro moderato (04:30)

- II. Adagio (03:29)

- III. Allegro (04:14)

- IV. Menuetto – Trio I – Polacca – Trio II (06:44)

-

- I. Allegro moderato – II. Adagio (06:47)

- III. Allegro (03:33)

- I. Allegro (10:02)

- II. Affettuoso (05:56)

- III. Allegro (05:44)

-

- I. Moderato (08:13)

- II. Adagio ma non tanto (03:32)

- III. Allegro (05:14)

-

- I. Allegro (07:27)

- II. Andante (03:52)

- III. Allegro (04:51)

- I. Allegro (05:02)

- II. Andante (03:39)

- III. Allegro (02:54)

Liner Notes:

Reviews:

“What Bindman and Lin achieve as a dual partnership… is breathtaking in its sheer precision and vitality.… Created well in time before the 300th anniversary of the Brandenburg Concertos, the young talents of the piano world will now dive into what could eventually be standard repertoire for piano duos.” Donald Hunt, Pianist Magazine

“Bindman’s transcriptions have a clarity and a cleanliness that Reger’s lack, although Bindman’s and Lin’s playing no doubt also is a contributing factor.… I can’t say that I enjoyed hearing this any less than I enjoy hearing Bach’s originals. … I will be interested to see if the appearance of Bindman’s transcriptions in print will attract other musicians.… I think they can help us to hear these familiar works in new ways, and to gain a new understanding of them. For those reasons, I think they are valid, and Bindman and Lin make a great case for them.” Raymond Tuttle, Fanfare Magazine

“With an equal collaboration between the two instrumentalists, using the full potential of the modern piano, to convey the unique writing and character of each concerto, the six concertos by both pianists Eleanor Bindman and Jenny Lin were arranged ( 1-3-5-6-4-2), that they create a fascinating listening series. Because Bach’s Brandenburg Concerti were never intended to be performed as a continuous series, their order is of little importance. You should not miss this version. It is very original and very, very special. Highly recommended.” Michael Dutrieue, Stretto

“Eleonor Bindman’s new transcription of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos highlights their polyphony, imagining how Bach might have distributed the score if he had created four-part inventions for piano duet.” Lisa Flynn, WFMT Chicago

“…pianists are going to greatly enjoy Eleonor Bindman’s new piano duo arrangement of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Six Brandenburg Concertos. … excellently recorded and immaculately balanced recordings…” David Denton

“…an interesting audible vitality of blending and differentiating voices…[Bindman] achieves a full and interesting sounding score… [The Brandenburg Duets] adds greatly to the two-piano repertoire, which thrives as a four-hand performance –no orchestra necessary.” Ilona Oltuski, GetClassical

“Eleonor Bindman's arrangement is outstanding…Bindman and Jenny Lin really lean in to this freedom, swinging when Bach allows, and never staid or boring when things get more thoughtful or academic. … Though she may have started with purely pedagogical reasons for bringing this music to four hands and a piano keyboard… Bindman and Lin are obviously having too much fun here for it to be just that. And that makes it even more pleasurable for us to listen to.” Dean Frey, Music for Several Instruments

“Eleonor Bindman has done a wonderful job for many musicians with her "Brandenburg Duets" project: a transcription of Bach's Concertos Bach for 4 hands… The result is playfully as fresh and new as authentic and convincing. Balanced in sound, perfectly attuned to each other, the version reveals new sides to these works, and the pianists equally do justice to the solos as well as the tutti with four hands, so that it would be a real pleasure for Bach. The hope is to see the transcription published by 2020 in musical form - it would be a stroke of luck for the four-hand repertoire and its lovers. A wonderful recording.” —Piano News

“I really enjoyed listening…the transcriptions are marvelous.” —Simone Dinnerstein

“Only pianists of the highest caliber could deliver these performances. Nothing I heard in these arrangements seemed out of place, and the phrasing and dynamic shaping of the lines were exceptional.… complete and very musical. It will give you a fresh look at some of Bach’s greatest works in piano arrangements that work quite well.” —James Harrington, American Record Guide

“Bindman’s transcription of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos is a significant accomplishment. It reflects Bach’s writing more than Reger’s romanticized arrangement by preserving the interaction between the varied soloists of the original pieces and by reserving the force of the piano’s bass for interpretive impact. Bindman also achieves her goal of making both piano parts equally engaging to play. Debuting The Brandenburg Duets through this exceptional recording, rather than through a published score, not only exhibits the insightfulness of Bindman’s decisions in preparing the arrangement, but also serves as an excellent vehicle to promote this much-needed contemporary transcription.” —Krystal J. F. Grant, International Alliance for Women in Music Journal

“Do you really need a new edition of more than 1000 original compositions by Johann Sebastian Bach? Certainly - but only if it is as brilliant as Eleonor Bindman’s new transcription for four-hand piano of the famous "Brandenburg Concertos". The Latvian-American pianist has succeeded in writing a version that focuses on the polyphony of the six concertos. The result is the "Brandenburg Duets", which Bindman recorded together with pianist Jenny Lin. The recordings are as successful as the arrangements themselves. The two pianists are remarkably precise, literally melting together, yet pleasantly relaxed and with unmistakable joy in playing. The original character of the compositions remains, while at the same time they acquire new facets through the sound of the modern piano.” —Sal, Kulturnews

Buy/Listen:

Tchaikovsky: The Seasons

Eleonor Bindman’s third CD issued by the MSR Classics label – her rendition of Tchaikovsky’s lyrical cycle “The Seasons” and two bravura piano transcriptions (one by Franz Liszt and one of her own) of his music to Eugene Onegin.

“You will certainly never tire of the recording by Eleonor Bindman [who] cultivates a beautifully centered full tone as she conveys to us the essential character of each of these charming pieces.” —Atlanta Audio Society

Tracks:

-

The Seasons, Op. 37b

- January: “By the Fireplace”

- February: “Carnival”

- March: “The Lark’s Song”

- April: “The Snowdrop”

- May: “May Nights”

- June: “Barcarolle”

- July: “The Reaper’s Song”

- August: “The Harvest”

- September: “The Hunt”

- October: “Autumn Song”

- November: “In the Troika”

- December: “Christmas” Solo piano arrangement by Eleonor Bindman

- Waltz from Eugene Onegin Tchaikovsky – Liszt

- Polonaise from Eugene Onegin

Liner Notes:

- January: Darkness is enveloping our peaceful corner by the fireplace. The last sparks are fading and the candle has ceased burning.

- February: Soon the feast of the winter Carnival will sweep through the village!

- March: The boundless spring sky resounds with the songs of larks.

- April: The pale blue snowdrop blossom grows out of thinning snow; a farewell to bygone tears and a welcome of new happiness.

- May: What an enchanting night! After the northern storms have gone, May comes forth its all its beauty and exhilaration.

- June: Come to the seashore, where the waves will caress our feet and the stars will glow with mysterious melancholy.

- July: A peasant reaper in the fields sings: “Swing, my arm; work, my shoulder! You, southern wind, cool my face off!”

- August: The farmer families begin their harvest, mowing down the rye at the root. The haystacks crowd the fields and the music of the cartwheels squeaks all night long.

- September: It’s time, it’s time! The horns resound, the horses are mounted at the break of dawn and the hounds tug at their leashes in anticipation.

- October: Autumn has arrived. The yellow leaves of our poor garden are flying in the wind.

- November: Do not look at the road with such longing, and don’t try to catch up with the troika. Stifle the disquiet in your heart forever!

- December: Once, on Christmas Eve, maidens would make a wish, taking off their slipper and throwing it outside the gate.

Buy/Listen:

Modest Mussorgsky

Included in Ms. Bindman’s debut recording, Three Works by Modeste Mussorgsky, are his famous masterpiece “Pictures at an Exhibition,” Ms. Bindman’s piano transcription of his orchestral tone poem “A Night on Bald Mountain” and the composer’s own piano arrangement of a lesser-known orchestral sketch, “Intermezzo in Classical Style.” This recording reflects Ms. Bindman’s passion for Mussorgsky’s music as well as her interest in the piano’s capability to assume the guise of a full symphony orchestra, as all three pieces exist in both instrumentations. The artist’s own piano rendition of “A Night on Bald Mountain” is a faithful version of the original. It is published by Carl Fischer, Inc.

Tracks:

- Intermezzo in Modo Classico Pictures at an Exhibition

- I. Promenade 1 - II. The Gnome

- III. Promenade 3 - IV. The Old Castle

- V. Promenade 3 - VI. The Tuileries

- VII. The Ox-Cart (Bydlo)

- VIII. Promenade 4 - IX. Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks

- X. Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle

- XI. Promenade 4 - XII. The Market Place in Limoges / The Catacombs

- XIII. The Hut of Baba Yaga - XIV. The Great Gate of Kiev Transcription by Eleonor Bindman

- A Night on Bald Mountain

Buy/Listen:

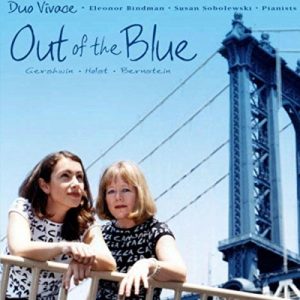

Duo Vivace: Out of the Blue

“Out of the Blue” is an exciting recording celebrating Ms. Bindman’s 10-year partnership with the other half of the piano team Duo Vivace, Ms. Susan Sobolewski. The centerpiece of this release is Gustav Holst’s 2-piano transcription of “The Planets” – a substantial effort for all involved and a revealing example of how the texture of an orchestral work can come through with unexpected clarity via two well-coordinated keyboards. Framing “The Planets” are two 4-hand jewels: the delightful “Candide Overture” of Leonard Bernstein and Gershwin’s deservedly ever-popular “Rhapsody in Blue.”

Tracks:

-

Leonard Bernstein:

- Overture to Candide Gustav Holst:

- The Planets, Op. 32: I. Mars, The Bringer of War

- The Planets, Op. 32: II. Venus, The Bringer of Peace

- The Planets, Op. 32: III. Mercury, The Winged Messenger

- The Planets, Op. 32: IV. Jupiter, The Bringer of Jollity

- The Planets, Op. 32: V. Saturn, The Brigner of Old Age

- The Planets, Op. 32: VI. Uranus, The Magician

- The Planets, Op. 32: VII. Neptune, The Mystic George Gershwin

- Rhapsody in Blue

Liner Notes:

Buy/Listen:

Left at the Fork in the Road

A broad overview of the Sean Hickey’s works for chamber and chamber orchestra configurations. Left at the Fork in the Road, released on Naxos American Classics, has met with critical acclaim throughout the world and was a Billboard charting release in its first weeks, a rarity for new music.