Flashback to the 1990s: I was hanging around between rounds of a piano competition and overheard a participant asking a judge why she has been eliminated. The judge, Israeli pianist Ilana Vered, answered matter-of-factly: “The rhythm wasn’t clear in the beginning of the Beethoven. How could we ignore that?”

This may seem harsh but so is the reality of the competition world. The first couple of rounds are all about weeding out those who make technical or stylistic errors. Interpretation is a matter of taste but there is no disputing wrong notes, faulty rhythm or any inconsistency with the composer’s intentions.

I am often surprised at hearing performances – even by famous pianists – where the rhythm and tempo of a piece only became clear after a few measures. To set the right atmosphere, musicians need to enter the flow of the piece ahead of the audience. We are normally taught to imagine the initial sounds before starting to play but that method, perhaps counterintuitively, is not the best way to prepare. A more effective start will happen if we mentally recall a later section of the piece, where the tempo and emotional charge are already well established.

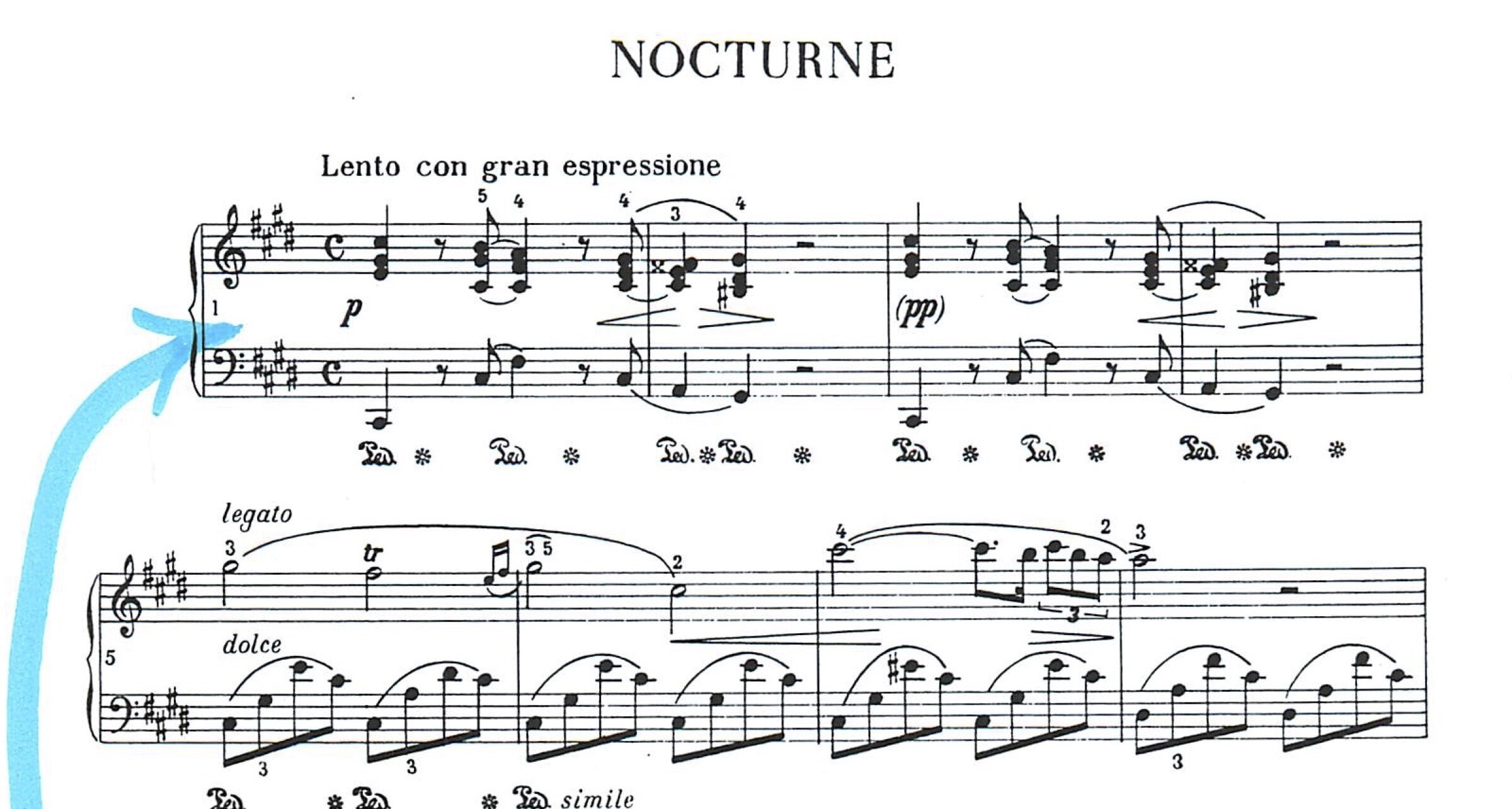

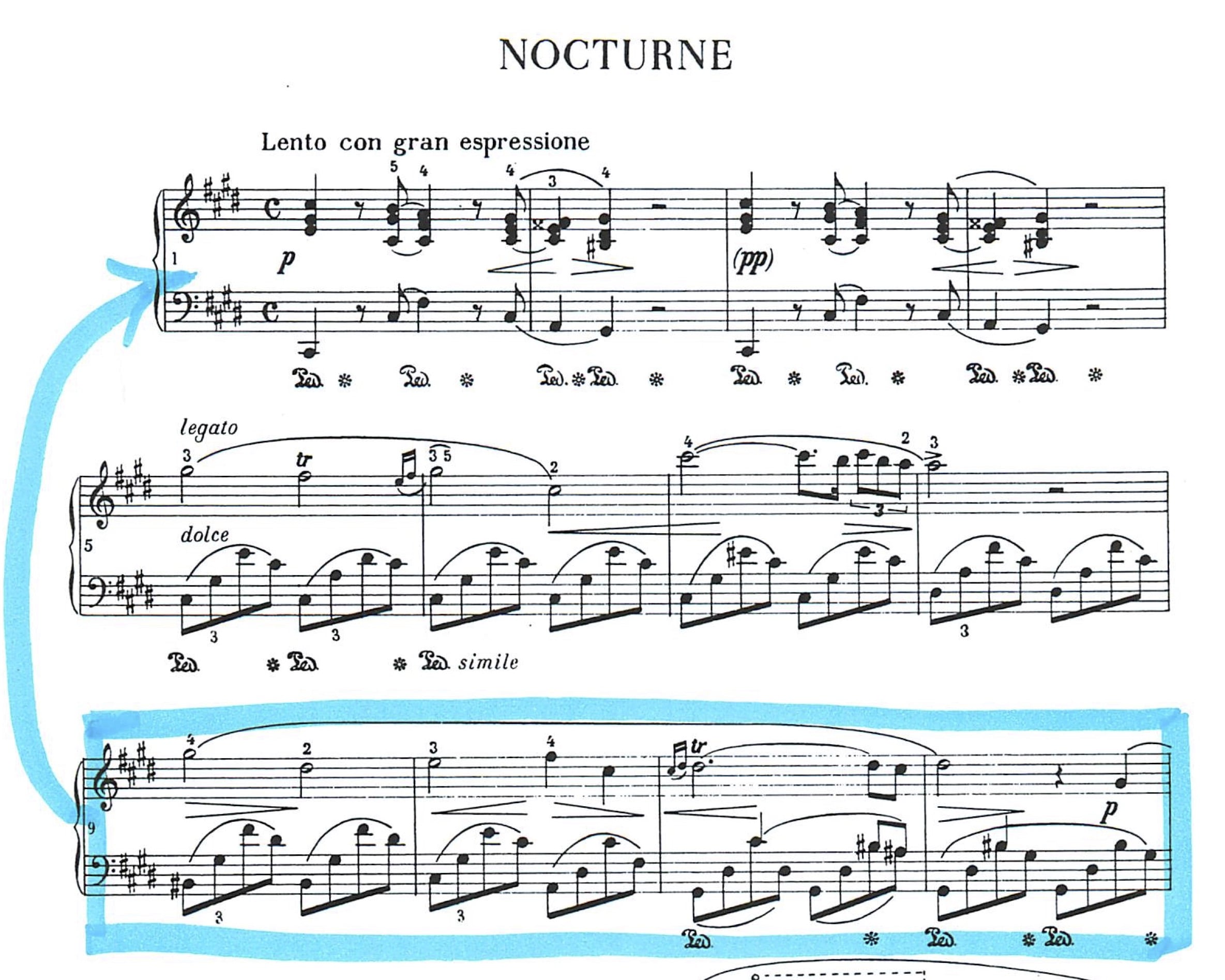

Most of us know about counting off a few beats before starting to play when we are sight-reading or learning a new piece. Once we get used to our piece, however, we often stop doing that and the first measures become vague, almost a “warm up.” That holds especially true when the score has long notes or rests. The best example of such an incoherent start in my teaching practice has been Chopin’s posthumous Nocturne in C# minor. I rarely heard a rhythmically correct execution of the first 2 measures:

Here we have a soft, fragmented introduction, which is exactly why we need to think more toward the middle of the first statement – perhaps mm. 9-12 in order to get the right beginning flow. Our associative memory will feel the momentum of the left-hand accompaniment and we should begin with that reference in mind.

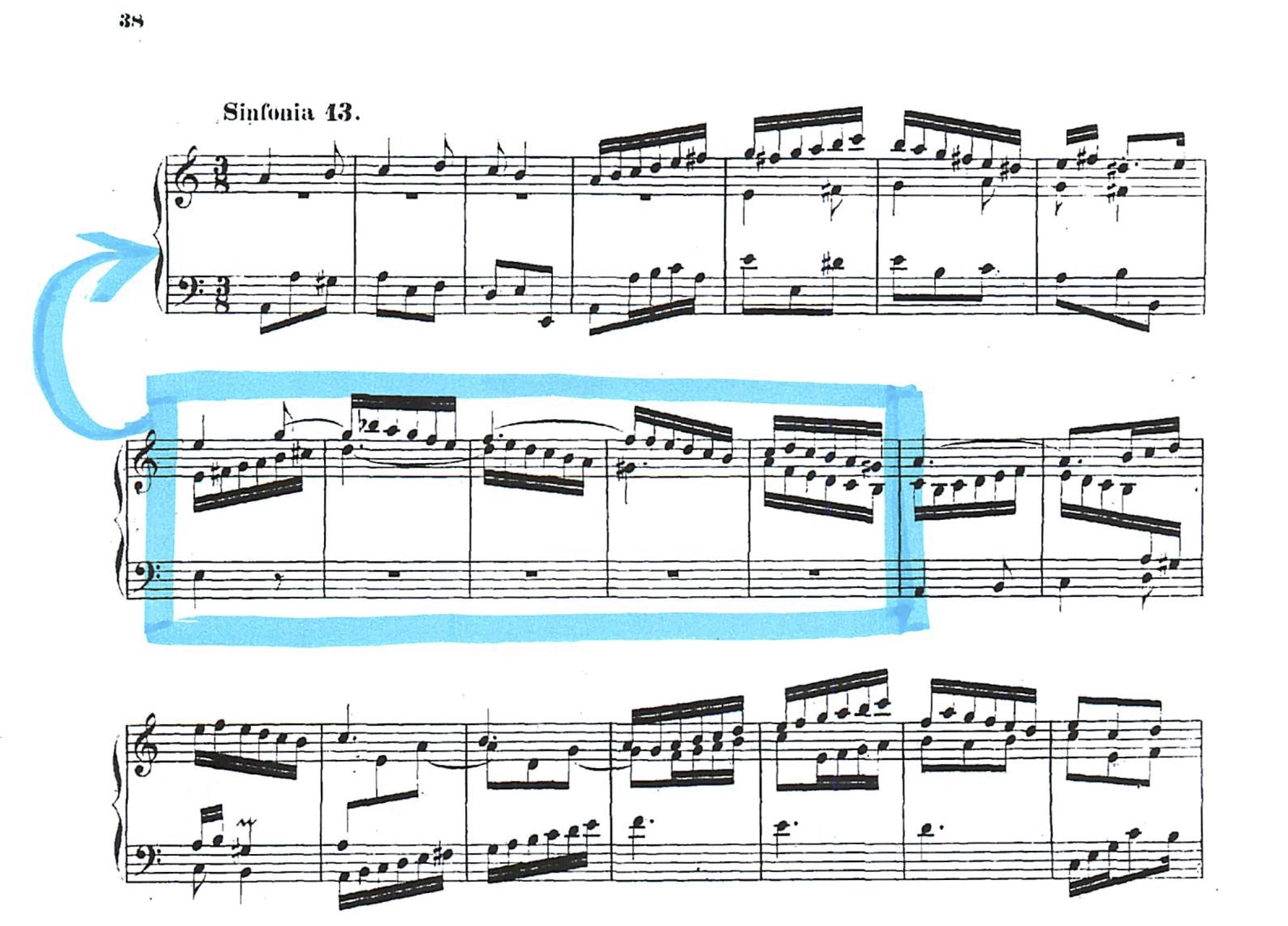

J.S. Bach’s Sinfonia No. 13 in A minor, below, will likely sound stiff in the beginning unless we imagine mm. 8-12 before starting. Those running 16th notes will shift our perception and breathe life into the first three measures: we will play a continued, well-shaped phrase and establish the right motion from the start.

Even our beloved Adagio cantabile from Beethoven’s “Pathetique” Sonata would benefit from some creative preparation. Although the 16th notes are there from the beginning, the music may still sound stagnant for the first few measures.

Try experimenting with two approaches to establishing the flow before starting: first by just counting off 2 measures starting, and then by mentally “hearing” measures 7-8 as a lead-in. And look for good places to use as “lead ins” for each piece you play. The difference may just amaze you.