Polyphony reigned supreme in the baroque period and most of us understand it as a complex texture of several equally important voices. Those voices, often introduced one by one (as in a fugue), are constantly intertwining, separating, moving in parallel or contrary directions and changing registers. Layers of their linear, “horizontal” movement create “vertical” harmonies, resulting in unique ever-shifting textures which can be overwhelming as our ears and brain try to “keep track.” Some people have trouble “liking” a fugue because it’s easier to focus on a nice melody and soothing accompaniment of a Chopin Nocturne or a Beatles song. Others have more affinity for polyphony and enjoy its uplifting effect as one may enjoy looking at a huge luminous tapestry for its overall effect, without knowing exactly how it was made.

Analyzing Bach’s Cantatas or Brandenburg Concertos requires extensive music theory training, usually the domain of composers, conductors and keyboardists who deal with complex scores regularly. Most non-professional pianists don’t need that level of expertise but we would all benefit greatly from understanding how the pieces we play are constructed. We need to study our scores otherwise we’ll just be playing notes instead of making music, like a precocious child or a trained parrot reciting Hamlet’s monologue. Impressive but surely devoid of whatever meaning Shakespeare aimed to convey.

As a pianist and arranger, I normally look at several voices at once and try to assess “the big picture.” Then in 2019, while transcribing the complete Cello Suites for piano, I spent months focusing on one musical line at a time and the smallest patterns clearly emerged as a key to understanding Bach’s language. Seeing how subtly yet mathematically he manipulates those “building blocks” in a cello part led me approach his other works from the same perspective. Interestingly, it turned out that much of Bach’s keyboard music can be studied with minimal theory background: all we need is to be able to recognize patterns.

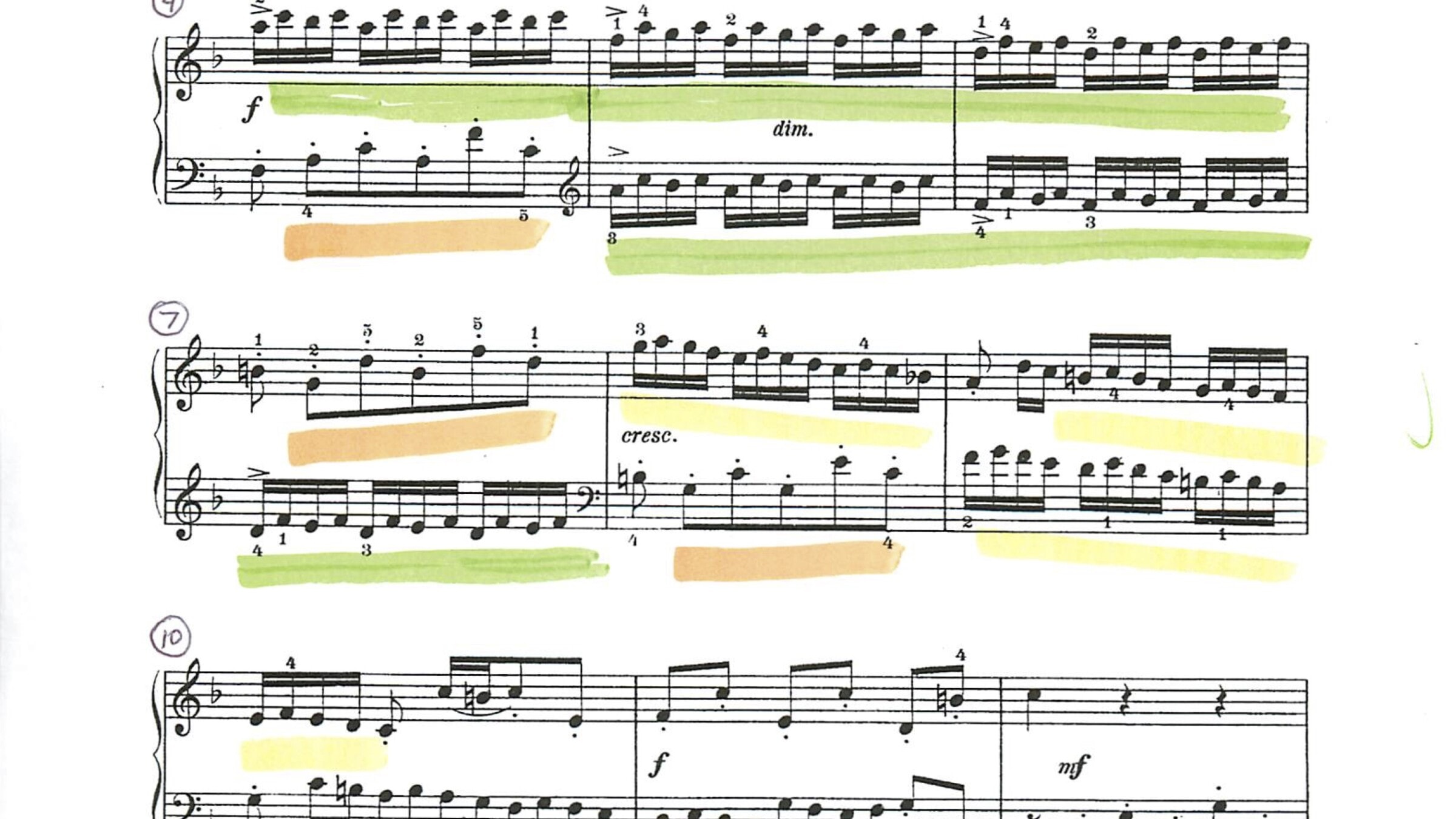

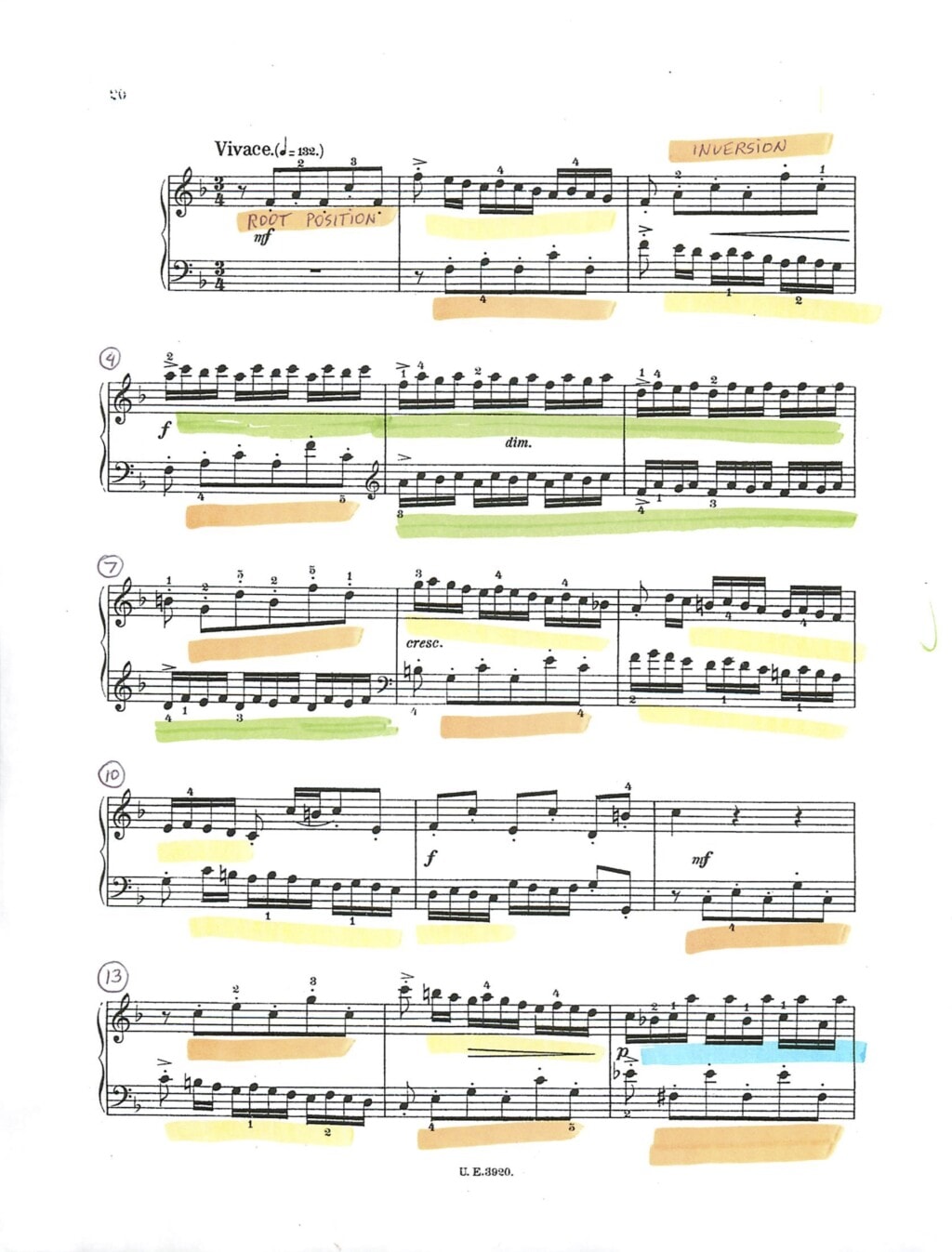

I would like to share some examples of simple analysis with you, in hope that this approach will be useful in getting you to look “deeper” into your scores on a regular basis. To start with, here is a visual study of a piece I teach to all of my students, the F major Invention No. 8 which I also feature in the “Piano Tips” video.

Another wonderful specimen – the Prelude from Cello Suite No. 1 – is usually analyzed by cellists harmonically, showing how the notes form different chords. Since that type of analysis is habitual for a pianist, I was more interested in breaking down each 2 beats into 2 significant elements which Bach later uses to develop the entire movement and provided a sample analysis at the beginning of my Cello Suites for Piano Volume. See the analysis here.

For an example of partial analysis, read the comments to another transcription of mine: “Affettuoso” from Brandenburg Concerto No. 5. Here, Bach develops a 6-note pattern to infuse more momentum and expression into a fairly static movement. See the analysis and download the work here.

After looking through these pieces and understanding their structure you’ll never go back to just playing the correct notes. You will gain a new appreciation of the composer’s craft, every note will be “in its place” and you will convey the music as it was intended. In turn, any listeners will pick up on the information you will be transmitting and will be equally engaged. Happy Practicing!