Back in the 1990’s, I was attending a Master Class of Oxana Yablonskaya – a pianistic powerhouse and Juilliard teacher – and heard her say to a student: “In Chopin, always learn the left hand first.” This phrase rang true and became one of my own teaching mantras.

Chopin’s unique gift for melodic and sentimental communication is best represented by his miniatures: Nocturnes, Mazurkas and Waltzes. In those compositions, the beautiful “cantabile” (singable) melodies entice us. The monophonic sequence of notes makes sense, our ears and fingers assimilate it easily and before we know it, that melody is etched into our memory.

The left hand, on the contrary, usually bears the burden of harmony, a domain more complex and not at all singable. Chopin’s accompaniment style is idiosyncratic: he rarely repeats it verbatim. If the harmony is the same, he will use a different inversion of the chord, add a note or two or transpose the bass up or down an octave. If he decides to alter the harmony, he can do it obviously with a whole new chord or extremely subtly, with a mere accidental. Normally there are already many sharps or flats in the key signature so the accidentals tend to proliferate, crossing over into double-sharps and double-flats. Even just looking at the bass clef part can become confusing, especially when Chopin introduces chromaticisms and enharmonic modulations, which he is so fond of.

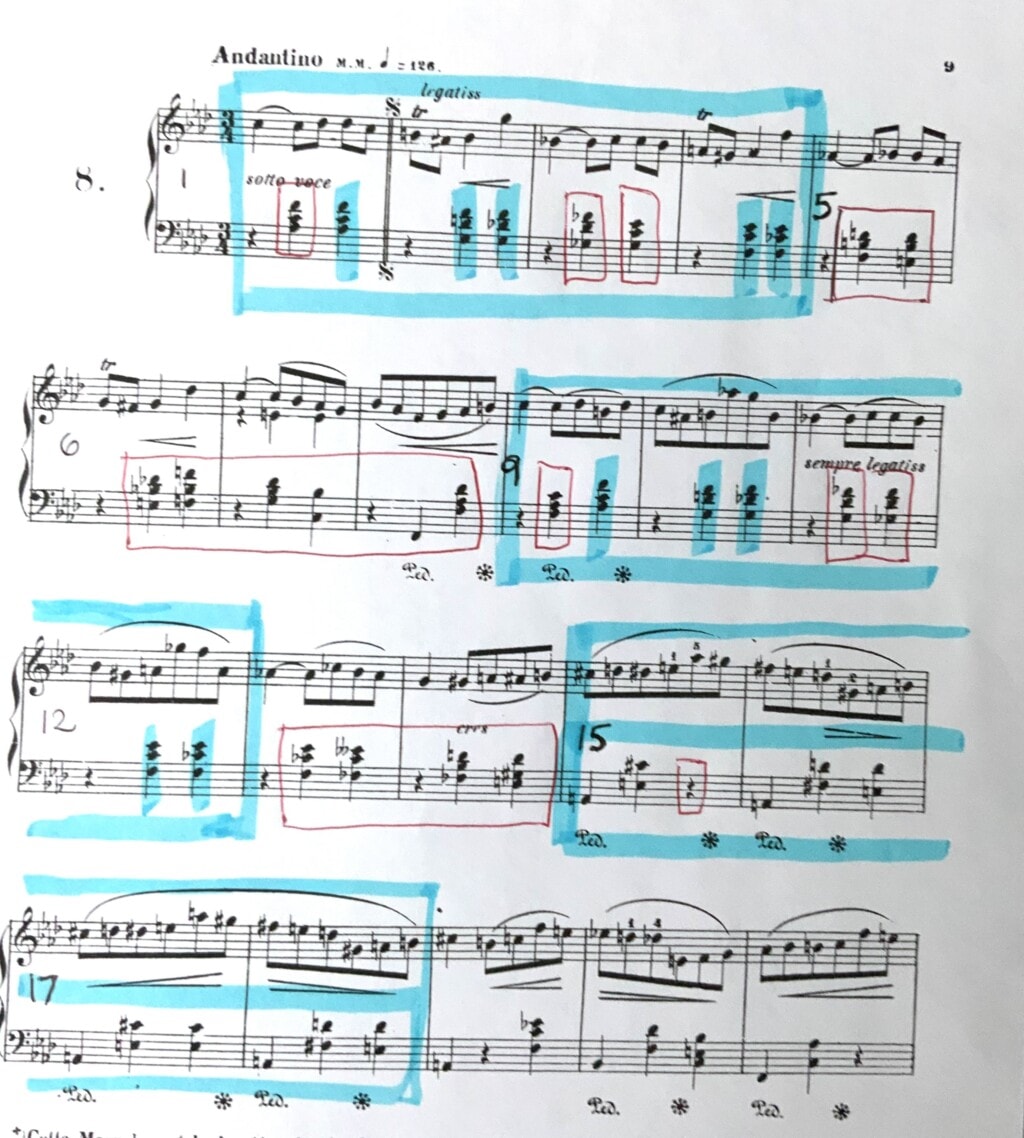

In this Mazurka Op. 68 # 4, Chopin uses descending LH chromatic chord progressions which don’t conform to any pattern and are very hard to memorize. The material in measures 1-4 (first blue box) repeats in measures 9-12 and whereas the RH melody is embellished in a similar way and can be memorized easily, the LH harmonies change or stay the same randomly. The same chords in mm. 1-4 and 9-12 are highlighted in blue and the changed chords are boxed in red. When learning the piece, I had to repeat the left hand a seemingly endless amount of times before it “came together” while my ear memorized the right hand after just a few repetitions.

When we practice those similar sections with randomly changing accompaniment, the left-hand part will often suffer from neglect. After all, the piece will still sound pretty good if the harmony is played “nearly” correctly. Very few listeners can spot those minute inaccuracies unless they know the piece really well. Most students and amateurs I have listened to over my years of teaching produced very sloppy Chopin accompaniments because they did not realize that the left hand needs a lot more practice time than the right.

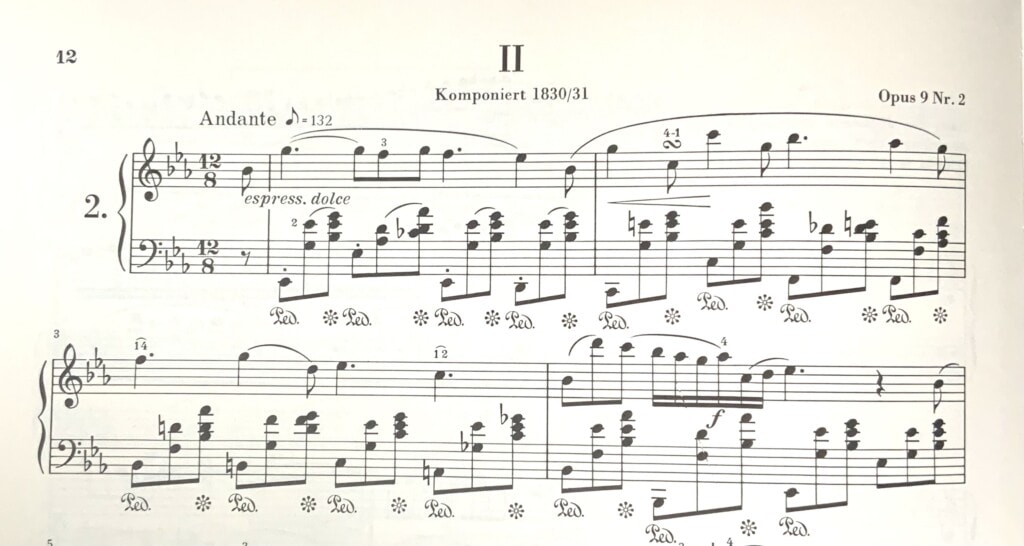

Even when the left hand doesn’t go through seemingly idiosyncratic changes, it is usually just more difficult to execute because of the sheer amount of notes to play and constant wide leaps. The beginning of the popular Nocturne Op. 9 No. 2 illustrates my point: just compare the number of notes and the difficulty of each hand. Even though Chopin repeats the LH almost exactly in the next 4 measures, you will still have to work hard to make sure it plays those bass notes and all the chord configurations correctly. So which hand needs to be practiced more? Aren’t we also likely to practice the RH first, just by force of habit and because we enjoy hearing that beautiful melody? If so, we will probably go over the LH just a few times, postponing working in earnest and hoping that the accompaniment will somehow come together in the future.

Ms. Yablonskaya’s “tip” is the only way to ensure that your Chopin will be learned securely. You should practice the accompaniment separately a number of times, ideally before even starting working on the melody. If you are an advanced pianist who doesn’t always need to practice hands separately, make an exception for the left hand in this context. I highly recommend deciding on a certain number of repetitions and using a practice log, just to make sure it gets done. I always do and it serves me well.