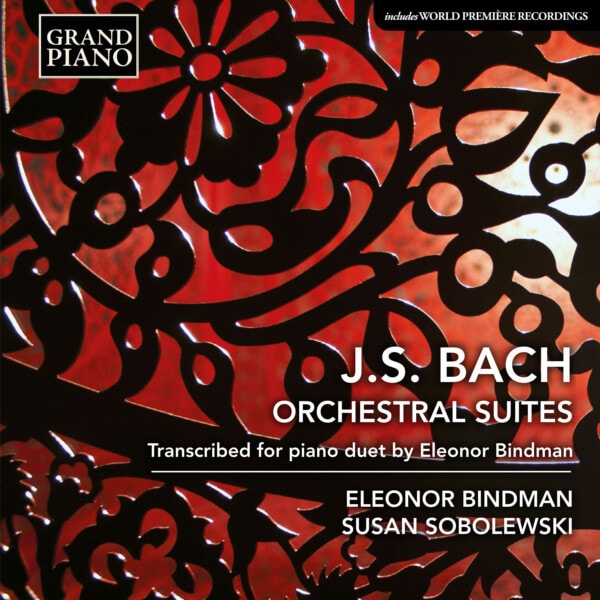

J.S. Bach Orchestral Suites: Transcribed for piano duet

$14.00

Eleonor Bindman’s new arrangement of Bach’s Orchestral Suites for piano duet follows her widely admired recording of the six Brandenburg Concertos. Once again, the transcription reimagines Bach’s writing using the modern piano, in this case a Bösendorfer. Bindman and her Duo Vivace partner, Susan Sobolewski, draw upon the suite’s dance movements to suggest how Bach might have distributed the material, ordering them for maximum contrast, and succeeding in conveying the music’s vitality and beauty in a new medium.

Tracks:

ORCHESTRAL SUITE NO. 3 IN D MAJOR, BWV 1068 (c. 1731)

- I. Ouverture

- II. Air

- III. Gavotte I – II

- IV. Bourrée

- V. Gigue

ORCHESTRAL SUITE NO. 2 IN B MINOR, BWV 1067 (c. 1738–39)

- I. Ouverture

- II. Rondeau

- III. Sarabande

- IV. Bourrée I – II

- V. Polonaise – Double

- VI. Menuet

- VII. Badinerie

ORCHESTRAL SUITE NO. 4 IN D MAJOR, BWV 1069 (c. 1725)

- I. Ouverture

- II. Bourrée I – II

- III. Gavotte

- IV. Menuet I – II

- V. Réjouissance

ORCHESTRAL SUITE NO. 1 IN C MAJOR, BWV 1066 (before 1725)

- I. Ouverture

- II. Courante

- III. Gavotte I – II

- IV. Forlane

- V. Menuet I – II

- VI. Bourrée I – II

- VII. Passepied I – II

All suites arranged by Eleonor Bindman (2022)

WORLD PREMIÈRE RECORDINGS

Liner Notes:

For many the music of J.S. Bach represents the final flowering of late Baroque style. His vast output of church music uses traditional contrapuntal writing with its horizontal construction featuring independent musical lines. However, his secular works do adopt more modern Italian-style characteristics with simple melody and accompaniment. Even here though there is still a strong contrapuntal flavour.

Bach’s final 27 years were spent as Thomaskantor, directing the music for four Leipzig churches. However, immediately prior, from 1717 to 1723, his appointment as Kapellmeister for the Prince of Anhalt-Köthen saw him produce a significant output of secular keyboard and orchestral music. It is unsurprising therefore that later writers attributed Bach’s four Orchestral Suites to the Köthen period. However, more recent scholarship has pointed towards at least revision work and probably also composition itself involving the Orchestral Suites taking place during Bach’s Leipzig years.

Bach’s music, traditional in its day was viewed as rather old fashioned after his death and it was not until the historical movement of the early 19th century led by composers such as Mendelssohn that Bach’s large choral masterpieces including the Mass in B minor and the St Matthew Passion became more generally known, appreciated and even revered.

Many of Bach’s autograph manuscripts were lost after his death in 1750. Opinions differ on why only four Orchestral Suites survive, for the form was immensely popular during his lifetime and it is likely he wrote more.

It seems the four Suites attained their final form during Bach’s Leipzig years although earlier versions may have existed. For example, there is stylistic evidence to suggest Orchestral Suite No. 1 in C major, BWV 1066 may have been the first composed of the four, at Köthen, although its surviving set of parts are in the hand of Bach’s main copyist Christian Gottlob Meissner and date from later, 1724–25, during Bach’s early Leipzig years.

Distinguished Bach scholar Christoph Wolff places Suite No. 1 in C major before 1725, Suite No. 4 in D major around 1725, with a later version 1729–41, Suite 3 in D major around 1731 and Suite 2 in B minor between 1738–39.

Significantly, Bach directed Leipzig’s Collegium Musicum for some years after 1729. This was a performance society with many student members which often met at Gottfried Zimmermann’s coffee house for performances of secular works. It would have provided Bach with a welcome alternative to his church music duties.

For today’s listener it is intriguing to conjure a scenario where the composer of rather serious church music in Leipzig takes opportunities to perform lighter dance pieces with his Collegium ensemble, some drawn from his earlier years as a court composer and others perhaps written or revised for the occasion.

All four Orchestral Suites are scored for strings, together with a variety of wind instruments about which there is some doubt concerning Bach’s original intentions. For example, cogent arguments exist against the traditional use of brass and timpani in Suites Nos. 3 and 4.

It is clear Bach worked hard to merge the French and Italian styles of his time. The Suites feature a potpourri of different dances – only Ouverture and Bourée movements appear in all four – and they feature a creative use of solo sections throughout. Bach predominately employs the two-part (binary) form of his day in the dance movements with characteristic dotted rhythms and fugal writing as established by Lully in the Ouverture movements.

Current historically informed performance practice is felt to better reflect the original Baroque playing manner than was routine in the 19th century. In this spirit Eleonor Bindman’s piano duet arrangements of the four Orchestral Suites allow for a clearer, more balanced tonal result than can be obtained from Max Reger’s piano duet version of 1907, hitherto the only well-known duet arrangement in print. In particular Reger attempts to include as many notes from Bach’s orchestral scores as possible, generally giving the primo duet part the lion’s share and leaving the secondo player only the remaining relatively simple bass lines, often doubled for added sonority. Bindman redistributes Bach’s notes more evenly between both players, sometimes relocating important counterpoint to allow the secondo player to take these notes without colliding with the higher primo part. In turn, this balances the overall piano sonorities more evenly across its whole range. Furthermore, the piano writing becomes simpler to perform, allowing for more stylish and elegant outcomes.

ORCHESTRAL SUITE NO. 1 IN C MAJOR, BWV 1066

I. Ouverture

This regal and spacious movement assumes a slight hauteur. The characteristic dotted rhythms in the slow first section lead directly into a sprightly, sophisticated fugal section typical of Lully’s Ouvertures. The slower dotted rhythms return to complete the movement with satisfying elevation.

II. Courante. III. Gavotte I – II

The Courante employs a slow three-in-a-bar beat giving ample space for profuse decoration while the Gavottes provide a rather more energetic two- in-a bar.

IV. Forlane. V. Menuet I – II

With each bar containing ebullient constant quaver movement in the inner parts, the Forlane exudes quiet energy while the very polished, stately Menuets are more restrained.

VI. Bourrée I – II. VII. Passepied

Even more energetic, the Bourrées’ two-in-a-bar are fleet and insistent. The final Passepied is more grounded giving a strong sense of closure and good spirits.

ORCHESTRAL SUITE NO. 2 IN B MINOR, BWV 1067

I. Ouverture

The arresting mood of the opening dotted rhythms builds on the B minor sonority and the subsequent busy fugal writing is infused with rhythmic complexities. This is all a far cry from the more traditional French manner of the Suite No. 1 Ouverture.

II. Rondeau. III. Sarabande

Energy levels reduce as the Rondeau, with its prominent up-beat and gentle swooping melody is followed by an almost reminiscent, slow and lovingly crafted Sarabande.

IV. Bourrée I – II

There is repressed excitement in the quicker beat of these two dances, but the music is nevertheless solidly grounded. Bourrée II features solo flute decoration before Bourrée I returns.

V. Polonaise – Double. VI. Menuet

The steady quaver tread of the Polonaise is balanced by flute solo decorations in the Double. The Polonaise then returns. The following Menuet adopts a similar three-in-a-bar and complements the previous Polonaise in mood.

VII. Badinerie

This famous movement, featuring flute solo virtuosity, combines drama and joyful ebullience in equal measure.

ORCHESTRAL SUITE NO. 3 IN D MAJOR, BWV 1068

I. Ouverture

This thoroughly joyful movement resonates with good humour. The fugal section, interspersed with solo episodes, scampers crisply with high spirits. The dotted rhythms of the opening French Ouverture style then return briefly.

II. Air

Popularised by 20th-century violin virtuoso Mischa Elman as Air for the G String, Bach’s orchestral original floats more serenely with less intensity, a testament to his genius.

III. Gavotte I – II

Another famous movement, the Gavottes bristle with melodic brilliance and drive. Gavotte I returns to close off the movement’s ABA form.

IV. Bourrée. V. Gigue

The Bourrée relies on its very marked rhythmic motifs for propulsion, while the following Gigue picks up the momentum in a rollicking 6/8 time that builds excitement for a rousing conclusion.

ORCHESTRAL SUITE NO. 4 IN D MAJOR, BWV 1069

I. Ouverture

Harmonic richness dominates the opening dotted rhythm section in the grand manner. A very expansive fugal section follows, marked by 6/8 time jollity and permeated by woodwind solo sections. The slower opening material returns to conclude with regal gravitas.

II. Bourrée I – II. III. Gavotte

Less emphatic than the Bourrée of Suite No. 3, these Bourrées have a certain neatness and formality. Bouree II is characterised by a rolling bassoon part in quavers throughout. Formality is retained in the following Gavotte, with its ornamental coruscations easily accommodated within a stately beat.

IV. Menuet I – II. V. Réjouissance

A cadential feeling infuses both Menuets, giving a suitably conclusive mood at this late stage in the Suite. Menuet I returns to round out the overall ABA form. The final Réjouissance bustles in a good-natured manner with a fast, marked three-in-a-bar. Listen for the brief humorous cadential surprises near the end. —Rodney Smith

Reviews:

“If I were half of a piano duo, I would want to play these transcriptions with my partner.… They retain many of the qualities of Bach’s originals—the grandeur, the balanced grace, the songfulness, and the zest… There is nothing here that I did not enjoy. …transcriptions such as these help me to see the skeleton that supports the rest of the orchestral body. More than that, however, they are fun, and they celebrate the joy of amateur music-making, even though the performers on this CD are professionals of the first rank.” —Raymond Tuttle, Fanfare