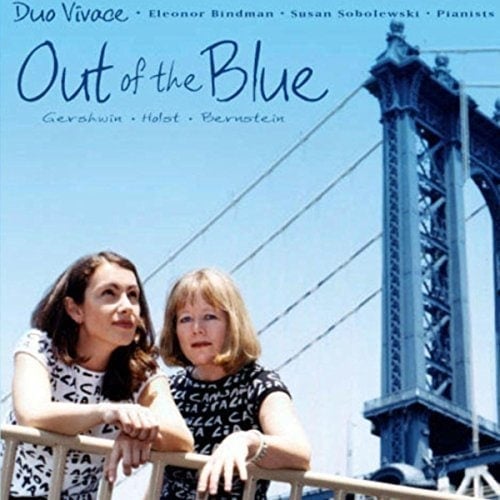

Duo Vivace: Out of the Blue

$10.00

“Out of the Blue” is an exciting recording celebrating Ms. Bindman’s 10-year partnership with the other half of the piano team Duo Vivace, Ms. Susan Sobolewski. The centerpiece of this release is Gustav Holst’s 2-piano transcription of “The Planets” – a substantial effort for all involved and a revealing example of how the texture of an orchestral work can come through with unexpected clarity via two well-coordinated keyboards. Framing “The Planets” are two 4-hand jewels: the delightful “Candide Overture” of Leonard Bernstein and Gershwin’s deservedly ever-popular “Rhapsody in Blue.”

Tracks:

-

Leonard Bernstein:

- Overture to Candide

- The Planets, Op. 32: I. Mars, The Bringer of War

- The Planets, Op. 32: II. Venus, The Bringer of Peace

- The Planets, Op. 32: III. Mercury, The Winged Messenger

- The Planets, Op. 32: IV. Jupiter, The Bringer of Jollity

- The Planets, Op. 32: V. Saturn, The Brigner of Old Age

- The Planets, Op. 32: VI. Uranus, The Magician

- The Planets, Op. 32: VII. Neptune, The Mystic

- Rhapsody in Blue

Gustav Holst:

George Gershwin

Liner Notes:

Leonard Bernstein’s Candide was originally conceived in 1953 as a “big, three-act opera with chorus and ballet.” The project took three years to complete and took on a lighter character in the process, becoming an operetta by the time of its Broadway premiere in December of 1956. The substantial score contained nearly two hours of music and was described by the composer as a “Valentine card to European music.” The overture summons up the spirit of Rossini, dances like the gavotte, the waltz, the polka and the mazurka abound, and the vocal numbers recall the Italian bel canto style.

The Candide Overture is an exhilarating experience; it captures the listener immediately, rushing through successions of thundering timpani, jubilant trumpets, tireless violins, romantic cellos and self-important French horns. Bernstein fully orchestrated and premiered this popular curtain raiser in the winter of 1956-57, conducting the New York Philharmonic. This four-hand piano version was created by Charlie Harmon, and the piece loses little in “translation.” Each register of the keyboard adds a voice to the burlesque jumble of the piece, especially the upper octaves as they imitate the brisk, glittering xylophone theme. The Candide Overture has become an indispensable part of every four-hand Duo Vivace performance, serving as a perfect and much anticipated encore in case the opening is spoken for.

In this triumvirate of Twentieth Century popular classics, Gustav Holst’s The Planets is most powerfully associated with large-scale orchestral sound—the breadth and variety of which is perhaps meant to evoke that of the cosmos. This seven-movement work, each representing a planet (except Earth and Pluto, not discovered until 1930), took place over the two-year period from 1914 to 1916. Given that point of history, it is difficult not to draw the conclusion that the onset of World War I influenced the opening movement, Mars, The Bringer of War, or similarly, did not inspire Venus, The Bringer of Peace, as a prayer to end the ravages of war. Indeed, other contemporary references include the dot-and-dash rhythmic patterns of Morse code telegraphed through Mercury, The Winged Messenger or the fading away of mystical, disembodied sound depicting Neptune, thought at that point to be the furthest planet from the sun. Each of the movements has its special astrological reference, which Holst took great pains to project musically. In Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity, the nature of the joviality is more universal, rather than personal in scale. Embedded between the robust, rollicking sections is a glorious hymn tune that elevates the joyousness to a higher spiritual plane. Uranus, The Magician was thought to be Holst’s reference and answer to Paul Dukas’ earlier masterpiece of 1897, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. The energy of the relentless scherzo builds to a feverish pitch before almost spinning out of control. What follows is pure magic–a timeless interlude before one more romp leads to the final crash of chords and ultimate dissipation. Saturn, The Bringer of Old Age, was reputedly Holst’s favorite, and what he considered his most successful movement. The irrevocable grinding on of time is so effectively depicted in the alternation of chords, and colors—first building up to human struggle and panic—and finally the release and acceptance that comes with old age. It is not a defeat that we hear, humans crushed by their condition. Rather, the music evokes fulfillment of transcendental sort—the sort that can only come with acceptance of the inevitable.

If the popularity of this work immediately conjures up the beating of timpani or the resonance of lower brass in our mind’s ear, it is interesting to note that before the public ever heard the orchestral version, The Planets was performed in its original two-piano version. Most likely, this version was the sketch Holst drew up to aid in the orchestration of the work. However, accounts of that first performance, by Vally Lasker and Nora Day, two of Holst’s pianistic colleagues at St. Paul’s Girls’ School in West London, attest to the effectiveness and excitement generated by this version. If any medium could rival the sound of the orchestra, both in breadth and in color, it is certainly the piano. If anything could rival the scale of a LARGE orchestra, it is certainly TWO PIANOS. In this form, The Planets as a work is both familiar and completely different, mimicking the very nature of the universe.

George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue is as synonymous with American music and New York City as the composer himself. One cannot escape references to this work. Whether strolling through Macy’s at Herald Square or listening to the famous United Airlines commercials, quotations from this American classic abound. Even the youngest of children have visual associations through the brilliant animation of this piece in the film “Fantasia 2000”.

When the great 1920’s bandleader, Paul Whiteman, also dubbed “The King of Jazz”, asked Gershwin to compose something for the famous Aeolian Hall symphonic jazz concert of February, 1924, Gershwin was against the idea and had put the request out of his mind. A press release of the concert in the New York Herald Tribune reminded Gershwin of his obligation, and he turned out Rhapsody in Blue in three weeks.

While the piece was originally composed for piano and jazz band, Ferde Grofe, the Whiteman band orchestrator tinkered with the instrumentation, scoring it as follows: 8 violins, 2 string basses, banjo, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, 2 pianos, drum, 3 saxophones, and 2 horns. Over time, the instrumentation was changed again and adapted to full concert orchestra settings. Eventually, the popularity of the work warranted even further transcriptions—including that of solo piano, and the version heard performed here, for one piano, four hands. Clearly, the great versatility of the piano allows us to imagine all the variation in timbres—from winds and percussion, to the great Romantic melodies drawn out in the strings. Regardless of the performing medium, the originality of ideas and the sheer inspiration behind this score keep re-inventing themselves with each version—not unlike New York itself!