Absolute

$14.00

J.S. Bach: Lute Suites BWV 996-998

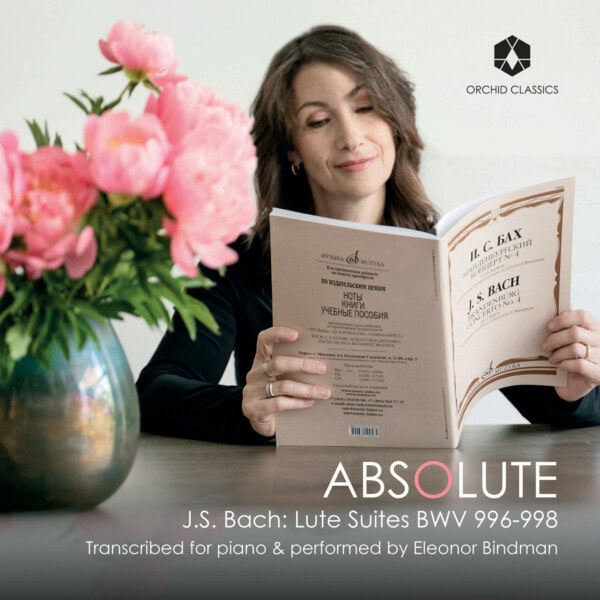

Transcribed for piano and performed by Eleonor Bindman

In this new album from pianist Eleonor Bindman, works by J.S. Bach originally composed for the lautenwerk (lute-harpsichord) are presented in piano transcriptions, offering a fresh perspective on some rarely explored masterpieces.

Highlights include BWV 997 and 998, featuring stunning fugues with ornate middle sections unlike typical keyboard fugues, and a heartfelt arrangement of “Betrachte, meine Seele” from St. John’s Passion, which serves as a moving conclusion to the album.

Fans of Eleonor Bindman’s previous transcriptions – such as The Brandenburg Duets and The Cello Suites – will appreciate this latest addition to the pianist’s catalogue, recorded on a Bösendorfer piano which truly captures the remarkable richness of Bach’s writing.

Eleonor Bindman writes, ‘Transcriptions can revive interest in original compositions, and I am hoping that a piano version of Bach’s Suites BWV 996, 997, and 998 will increase their popularity. There is no consensus as to exactly what instrument each suite was designated for, but the choices narrow down to either the lute or the lute-harpsichord, an instrument then known as “lautenwerck.” Existing autographs and manuscripts are mostly in staff notation with a few lute tablatures since only professional lute players could produce those. Recorded versions are usually titled “lute suites” and performed either by guitarists, lutenists, or harpsichordists. Just like Bach’s other solo collections, these suites present a technical and musical tour de force for their performers and deserve their rightful place alongside Bach’s suites for keyboard, violin, and cello.’

Tracks:

Lute Suite in E minor, BWV 996

- Prelude: Passaggio – Presto

- Allemande

- Courante

- Sarabande

- Bourrée

- Gigue

Lute Suite in C minor, BWV 997

- Prelude

- Fugue

- Sarabande

- Gigue

- Double

Prelude, Fugue and Allegro in Eb major, BWV 998

- Prelude

- Fugue

- Allegro

- “Betrachte, meine Seel” from St. John’s Passion, BWV 245

Transcribed for piano & performed by Eleonor Bindman

Liner Notes:

J.S. Bach’s music has always been subject to a kaleidoscopic variety of permutations, starting in the 1700s with his own frequent re-instrumentations of the same pieces. The 19th and early 20th centuries saw Liszt, Busoni, Siloti and Rachmaninov employing the new capabilities of the piano to create and perform their virtuosic transcriptions and paraphrases. In the swinging 1960s, The Swingle Singers, Jacques Loussier and Wendy Carlos expanded Bach’s sphere of influence into the domains of jazz and electronic music. Purists like Wanda Landowska, renegades like Glenn Gould, and thousands of other musicians found his works equally inspiring of awe and play, of homage and recreation.

Arnold Schoenberg called Bach “the first 12-tone composer” referring to the conceptual nature and the visionary quality of his music. Rosalyn Tureck played Bach on the harpsichord, clavichord, piano, the Moog and the theremin, asserting that his music is defined primarily by the principle of organization, not by a particular sonority or instrument. Indeed, Bach’s output is a paragon of Absolute music: compositions that represent nothing but music itself, disconnected from any extraneous “program” or idea. Even his sacred choral works wield their power over the listener not through the devotional context but through the synergy of melodic and rhythmic patterns, simultaneously engaging our emotions, minds and spirits beyond any graspable meaning. He crafts building blocks of a few interrelated pitches into melodic fragments, then extends them horizontally, layers vertically and juxtaposes polyphonically. These patterns merge into ever-shifting sonic energy fields, gateways into immaterial dimensions of the abstract, the Absolute. They have been traveling through time and space for over 300 years without losing their charge.

Transcriptions can revive interest in original compositions, and I am hoping that a piano version of Bach’s Suites BWV 996, 997, and 998 will increase their popularity. There is no consensus as to exactly what instrument each suite was designated for, but the choices narrow down to either the lute or the lute-harpsichord, an instrument then known as “lautenwerck.” Existing autographs and manuscripts are mostly in staff notation with a few lute tablatures since only professional lute players could produce those. Recorded versions are usually titled “lute suites” and performed either by guitarists, lutenists, or harpsichordists. Just like Bach’s other solo collections, these suites present a technical and musical tour de force for their performers and deserve their rightful place alongside Bach’s suites for keyboard, violin, and cello.

Suite in E minor BWV 996 closely resembles Bach’s keyboard suites in structure and texture and therefore was most likely written for the lautenwerck, not the lute. Bach assigns plenty of 16th notes and consistent counterpoint to the low voice, resulting in a rich texture which can only be ploddingly rendered on the baroque lute. The introductory movement is in two parts: Passaggio and Presto. The Passaggio combines Recitative and French Overture elements, punctuating improvisatory solo passages with dramatic chords in dotted rhythms. After a rest, new phrases occur in the same fashion and modulate until the last stretch of dotted chords ends on the dominant, setting up the Presto, a vivacious fughetta in 3/8 time. In this piano version, I added a few notes in the bass in measures 42-44, resulting in a full iteration of the subject and a smoother transition from two to four voices.

Allemande is the first of five traditional suite dances in BWV 996. Like most of J.S. Bach’s keyboard Allemandes, it is a tender story, a meditative palate cleanser between the dynamic Presto and lively Courante. I take advantage of the piano’s acoustical features here, as I do throughout this recording, prolonging some notes to expand implied counterpoint into a fuller, more imitative texture. The Courante’s faster pace and florid ornamentation also benefited from the piano’s capabilities. My rendition of this movement, with added runs and more density in the bass during repeats, results in a viscerally gratifying and virtuosic reading. The melancholic Sarabande sustains its introverted mood through many unexpected modulations and a prolonged middle section in B minor, Bach’s most tragic key. It is followed by the wonderful Bourrée, so beloved by guitarists. Transcribing Bach’s “greatest hits” such as this one is always daunting because the choice narrows down to being predictable (read: boring) or unpredictable (read: objectionable). Fortunately, the tradition of repeating Baroque dance movements allows for both, so to create a fun repeat I took a cue from Bach’s own treatment of the basic unit: a three-note (short, short, long) pattern which he uses incessantly in the upper voice. The long notes occur on every strong beat and have to be deliberately understated, creating a rhythmically ambiguous feel. In the last phrase, Bach juxtaposes the same syncopated pattern in the lower voice a beat later, clearly affirming that he was playing with rhythm all along. Compelled to join in the fun, I decided to repeat each section using a jazzy “walking bass” in the left hand. The energetic Gigue is our final clue that this suite was meant for the keyboard, its highly contrapuntal texture unplayable on the lute faster than Moderato. To invigorate this closing movement, I add octaves in the left hand for the repeats, imitating the double-stop effect of a baroque keyboard.

Suite in C Minor BWV 997 is traced to disparate versions, including a manuscript endorsed by C.P.E. Bach as “fur Clavier” and a copy of movements one, three and four in French tablature titled “Partita al Liuto.” Other than in the Fugue and a few “echoes” in the Sarabande, the lower part consists of single bass notes, making it equally suitable for a fretted or a keyboard instrument. The spirited Prelude opens with three exact repetitions of an upward sweep in C minor, establishing a no-nonsense attitude and verve reminiscent of the start of the D minor harpsichord concerto. It’s written in ritornello form, with prominent syncopations and unyielding drive, except for two fermatas on the D7 chord (secondary dominant) and the G major chord (dominant) which imply a break for improvisation. My recorded cadenza is built on previous material and includes an open-ended anticipation of the next movement. The dramatic Fugue features a wonderful subject of a five-note ascent from tonic to dominant followed by a five-note chromatic ascent continuing through the octave to the upper tonic. The chromaticism creates enduring tension which Bach skillfully dissipates through playful episodes based on the interval of a fourth and a lower mordent. It is an unusual da capo fugue structure featuring a beautiful B section with a textural layer of constant 16th notes typical in baroque lute parts, followed by a verbatim return of section A. The Sarabande bears a strong motivic resemblance to the final chorus of St. Matthew’s Passion. Each section starts with stately eight measures of rich orchestral texture which are balanced by eight measures of running 16th notes accompanied by single bass notes. The Gigue and Double of this suite are often presented as a single movement since the Double is always a variation of the preceding dance. I chose to record them as separate movements, repeating each one. Here, the upper voice of the Double presents an embellished version of the Gigue in shorter notes (16ths or semiquavers) and the lower voice changes registers and sometimes participates in the upper voice’s passagework. Going a step further, I “doubled down” on the Double, using passages of 32nd notes (demisemiquavers) to embellish the repeats.

Prelude, Fugue, and Allegro BWV 998 is the only set on this recording with an authenticated autograph, the front page of which reads “Prelude pour la Luth. ò Cembal, par J. S. Bach.” This unusual three-movement set in “celestial” Eb major with its key signature of three flats is believed to suggest a theological message of the trinity. Indeed, the remarkable Prelude is a treasure trove of structural and melodic references to the number three. It opens with a three-measure statement of triplets (the time signature is 12/8) over three E-flats repeated in the bass. In this piano arrangement, I opted for an Eb octave held for all three measures since that reflects Bach’s conception but could not be realized on either a lute or a harpsichord. As unusual as a three-measure unit is, Bach underscored this quaint structure further by writing connective material of three, two, or a combined five measures in length. Melodically, each measure of the main statement begins with a three-note lower mordent pattern (EbDEb, BbAbBb, GFG) outlining a downward inversion of a triad (Eb – Bb – G). Bach uses this three-note shape in almost every measure throughout the Prelude, shifting its placement, outlining more triads, repeating it twice or three times on the same note and steadily increasing its occurrence. This demonstrates a most striking example of the composer going through extreme efforts to emphasize a structural element. Between measures 39 and 40, the “Neapolitan” Fb major chord passing into an inversion of an F7 chord sounds so disjointed and inconsistent with the rest of the piece that I added three extra measures for a smoother harmonic transition, an improvisatory solution justified by the fermata.

The BWV 998 Fugue is, like its sister from Suite BWV 997, a grandiose da capo construction but because of the difference between C minor and Eb major, it’s not as intense and is more majestic. Here, the subject is a stately succession of eight quarter notes (crotchets) which starts from the Eb-D-Eb grouping of the Prelude and ends on Eb, within a range of only a fifth. The countersubject is laid out in eighth notes (quavers) and similarly lacks specific direction, so my preferred interpretation is one of tranquility, almost detachment, just allowing every line and turn of the architecture to unfold and settle on its pillars. The middle section here, just like in BWV 997, is enveloped by flowing 16th notes (semiquavers), an enhancement further transporting us into greater equanimity, as if receiving divine grace coming down from the Absolute. Bach artfully weaves the return of the subject into the last undulating passages of the middle section (mm 75-77) for a beautifully seamless da capo transition. This is decidedly the most sublime fugue I have ever played; experiencing it is akin to meditating. At the conclusion, one’s spirit is refreshed, exactly what Bach referred to as “the final end of all music” in his famous quote. Completing the BWV 998 trifecta, the Allegro in 3/8 time ended up being the most pianistically daunting of all the movements on this album for me. Despite the simplicity of the material, the right-hand perpetuum mobile lies so awkwardly on the keyboard that I suspect it was intended for the lute after all. The knotty and unusual hand positions strain the forearm so consistently that even practicing it at a slower tempo needs to be judiciously budgeted to avoid a case of “BWV 998 tennis elbow.” Be that as it may, finally mastering this movement will certainly result in a jubilant mood which the music is meant to convey.

The text of “Betrachte, meine Seele” invites our souls to contemplate their highest good as symbolized by the suffering of Jesus. This bass arioso from St. John’s Passion is originally scored to be accompanied by low strings, lute and organ continuo. The close proximity of the vocal bass range to the instrumental registers made adapting this work for solo piano quite challenging. Nevertheless, it sounds quite pianistic, the harmonic lute accompaniment creating a luxurious “romantic” feel. Since the arioso is very short, I took the liberty of repeating it in a higher register, as any pianist would naturally prefer to have the melody in the right hand. I am grateful to Stuart Arlott for suggesting this gem as a possible arrangement and hope that you will enjoy it as a final offering of this recording.

ABSOLUTE is dedicated to the memory of Lillian Firestone.

Eleonor Bindman

Reviews:

“The process of adapting music from one instrument to another, via transcription, is an art unto itself.… Eleanor Bindman expresses the hope that in presenting these versions of Bach’s music, her intentions and efforts will revive a broader interest in the music.… In transcribing music from the lute to piano there are aesthetic, artistic, and technical considerations facing the musician; Bindman caters well for all.… the tempo and voice clarity of the Allegro from BWV 998 are unmatched by plucked instrument players. How would Bach feel about these new versions of his music: all things considered, probably fairly chuffed.… There is no question that adaptation and transcription of original music can enhance and augment the appreciation of the original composition. … The present recording deserves serious consideration and audition. Listeners will not be disappointed.” — Zane Turner, MusicWeb International

“Eleonor’s new recording of the Lute Suites brings a fresh perspective on these rarely explored masterpieces, showcasing their intricate structures, rich textures, and emotive character on the modern piano.… Highlights include BWV 997 and 998, featuring stunning fugues with ornate middle sections unlike typical keyboard fugues, and a heartfelt arrangement of “Betrachte, meine Seele” from St. John’s Passion, which serves as a moving conclusion to the album.” —Frances Wilson, Interlude HK