My piano transcription of the Bach Cello Suites was the first faithful version of the complete Six Suites for the piano to be found in recordings or published music. One wonders, with the immense popularity of these works and plenty of arrangements for violin and viola plus selections for bass clarinet, ukulele, trumpet, marimba, guitar and bass recorder among others, why haven’t pianists been able to enjoy this wonderful music yet? Had the value of playing something so gratifying yet so simple on the keyboard, of studying a score so perfectly crafted and yet so easily understood not occurred to anyone?

The Cello Suites project grew out of my Stepping Stones to Bach arrangements which were motivated by the desire to help more amateur pianists play Bach successfully. After sitting next to private students week after week while they struggled with 2-part Inventions, it occurred to me that what seems like easy Bach to me must be quite difficult for them. Bach’s keyboard pieces, even the easier ones, usually involve counterpoint (two voices of equal importance moving concurrently), and coordinating the intricate voices is a very specific and challenging blend of mental and kinetic functions. Bach intended them for pupils like his sons who had “natural” ability and were undaunted by counterpoint. After all, very few people learned to play the keyboard in Bach’s times unless they were to become musicians (or belonged to royal or very prominent families and owned an instrument.) My students don’t have Bach’s genes and are just learning to play for leisure, so I decided to simplify some of Bach’s greatest masterpieces for their enjoyment. Transcribing Cello Suite movements for the Stepping Stones books was a no-brainer and after playing them myself I realized that the music felt idiomatically very suited to the piano and the experience was wonderfully gratifying.

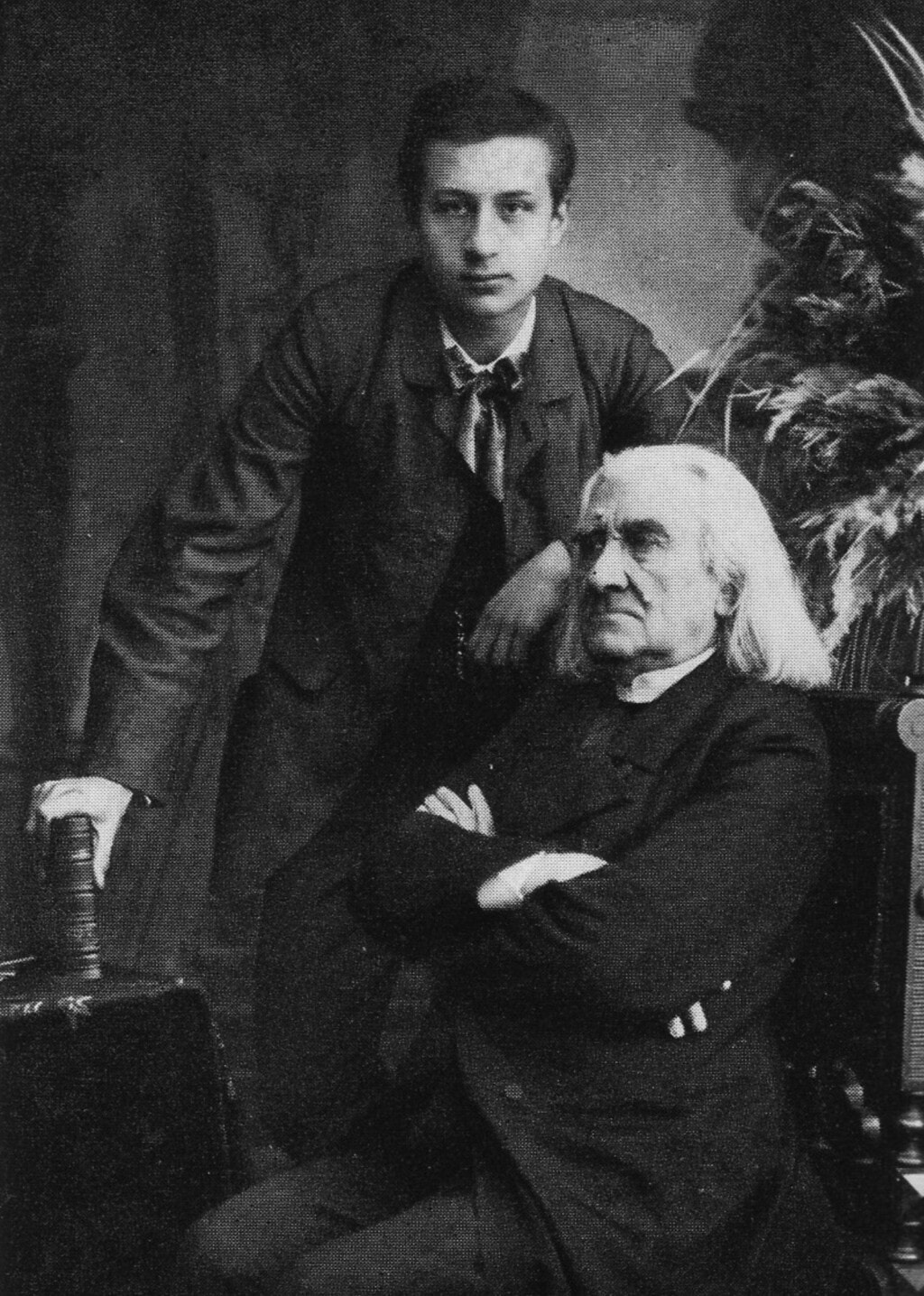

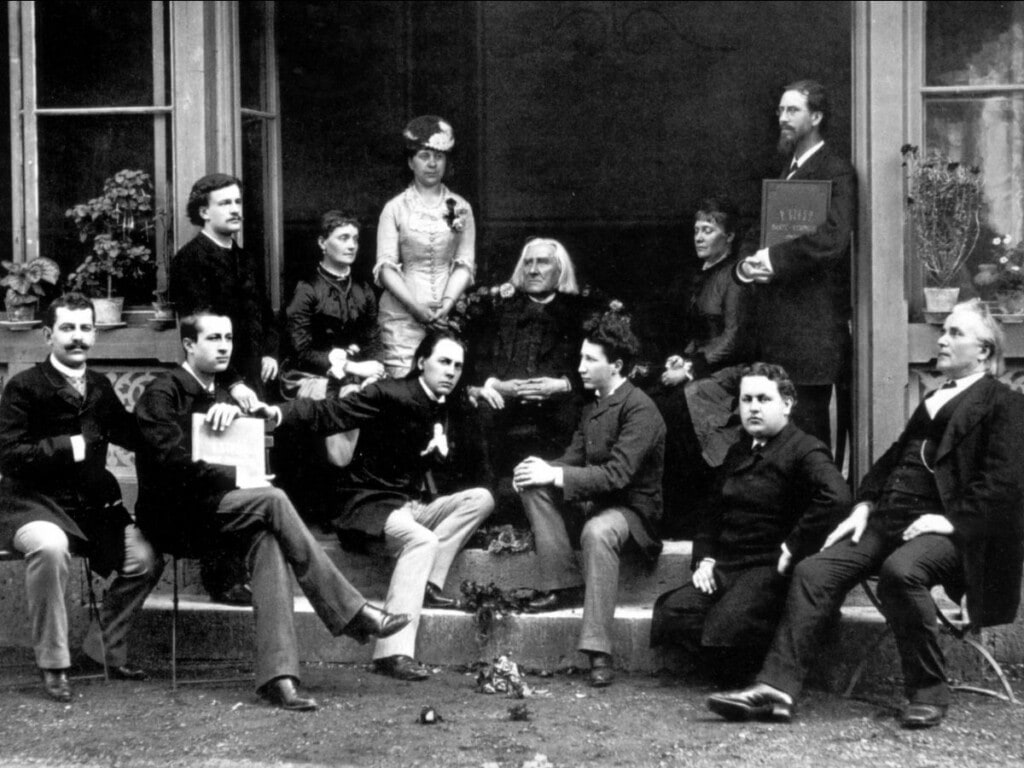

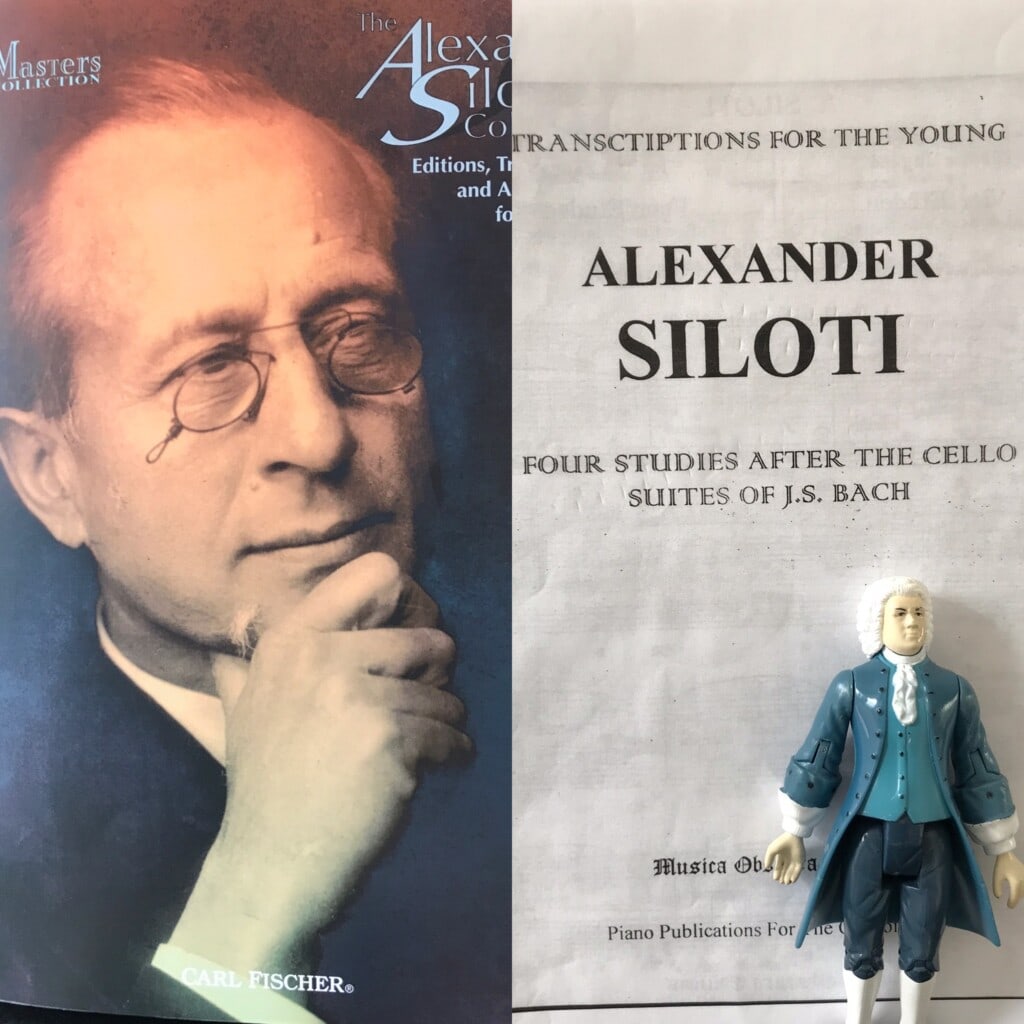

Alexander Siloti (1863-1945), an illustrious Russian pianist (and a first cousin of Rachmaninov), understood the value of the Cello Suites as potentially educational piano material a century ago. From 1883 to 1886 he was one of the favorite students of a certain superstar in Weimar…you guessed it, Franz Liszt. Inspired by the magnificent transcriptions and paraphrases of Liszt, Siloti eventually produced a collection of roughly 200 piano arrangements himself, a good percentage of which derived from Bach. As most virtuosos, he had very large hands and those transcriptions are technically ambitious – see this version of the Prelude from Cello Suite # 4 where each note is reproduced in double octaves. Yet the sublime and simple arrangement of Bach’s Prelude in B Minor from Clavier Büchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach is the one that stood the test of time (download it here). Here is a historic video of Emil Gilels playing it as an encore.

Finding Alexander Siloti’s “Four Studies after the Cello Suites of J.S. Bach” was the final “stamp of approval” I needed to put this project in motion. He chose the famous Prelude and the Courante from Suite #1 in G major, plus the Prelude and Bourrées from #3 in C Major and transformed them in the same way that I envisioned for the complete suites. The set was published by “Musica Obscura Editions” in 1914 under the heading “Transcriptions for the Young.” Siloti makes no changes or additions to the original score, except for amplifying the last few notes of the Preludes by adding a couple of octaves – you can’t take the Liszt out of a disciple. You can download the complete set here, and see for yourself. These four pieces are an amazing resource not only for the young, but for piano students of any age. They contain the key to Bach’s language in its most laconic and elegant form besides just being great ways to keep the fingers limber. I trust you can easily understand why I decided that all 36 movements of the 6 Suites deserve to be presented to pianists in an easy-to-read form.

The process of transcribing, editing and recording the Cello Suites took about 9 months – an appropriate gestation period – and each stage was fascinating and enriching. I learned and assimilated an enormous amount of theoretical, interpretive and philosophical information about Bach’s music in a way I never had before because, for a change and atypically for a pianist, I only processed it one note at a time. Without seeing several voices, the implied polyphony of each line becomes crystal clear. Without hearing several voices, we can learn how listen to each note really well. It’s an experience which takes you right to the source of it all and I’m sure cellists will agree. I could go on and on with my new discoveries but the purpose of this particular newsletter is to introduce you to the origins of this project. I will discuss transcribing and editing, interpretive choices and the recording process in the future.

In the meantime, I’d like to leave you with a preview of the score: here is a download of the Gigue from Suite #6 with a corresponding video which many of you have probably already seen on YouTube: